The Heart Is A Hyperdrive: How Emanuel Swedenborg Talked To Aliens In 1758

And shaped the modern spiritual imagination

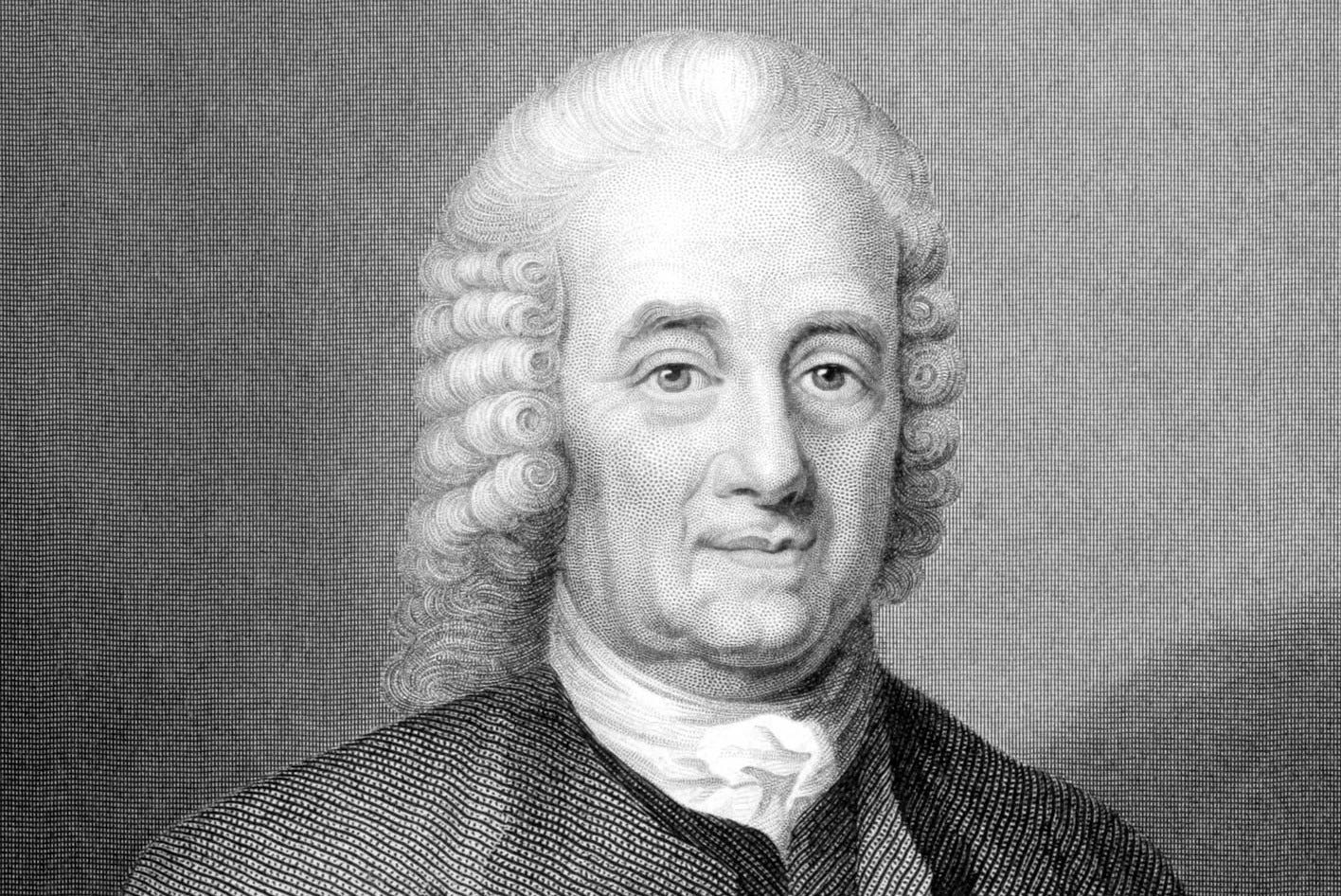

Emanuel Swedenborg had his first great spiritual vision on Easter weekend in 1741 at the age of 53, when the Son of God appeared to him.

He was already known as a psychic, demonstrating his powers on public occasions. Philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote about his displays of clairvoyance, such as his vision of a great fire that was really burning in faraway Stockholm. Swedenborg developed these skills as a form of espionage. Remote viewing, a la The Men Who Stare At Goats, was considered a legitimate form of intelligence-gathering at the time. Much else of his working life is rumor. Historians of his life report “vague but persistent claims that he participated in secret political, diplomatic, and Masonic affairs,” Swedenborg historian Marsha Keith Schuchard writes.1 Swedenborg was a member of the Hat Party, a supporter of Jacobites and French policy and Louis XV, who personally funded the anonymous publication of Swedenborg’s Arcana Celestia in London.

The capital of England is also where Swedenborg got recruited to diplomatic service, navigating “complex and often dangerous political byways,” and London is also where he died in 1772. “That he wrote in Latin was both an impediment and an aid to the spread of his work: it restricted his audience to the educated and it relieved official anxiety that his writings would corrupt ‘simple folk,’” Jonathan Rose and Ollie Hjern write.2 Publication in London ensured that Swedenborg’s ideas crossed the Atlantic to North America in time for a newly-independent nation to adopt them.

A spiritual biography of Swedenborg begins with Swedish Protestantism. He was a Mason of the Franco-Scottish school, Schuchard notes. Established by the exiled Stuarts, this branch of Masonry was distinct from the English Masons by drawing “upon older traditions of Kabbalistic and Rosicrucian symbolism” to “maintain mystical morale” among the “dispersed brethren” of the Jacobite rebellions. So-called “second-sight” was one of their spiritual practices. Through “his erudite brother-in-law and intellectual mentor,” Swedenborg “also gained unusual access to heterodox Jewish mystical lore.” These studies made Swedenborg “familiar with the Kabbalistic meditation techniques which produce trance states, spirit communication, and clairvoyance.” His knowledge of letter-number transpositions in Kabbala was also useful for diplomatic codes and ciphers. Swedenborg was talented at “physiognomical analysis of facial expressions and body postures,” Schuchard writes. In one passage, Swedenborg observes that the “protruding lips” of aliens are proof of their honesty. At the time, that passed for scientific observation.

His impact was far-reaching. At the end of his life, Swedenborg “contributed to the efforts of a group of radical Rosicrucians in Hamburg and Kabbalistic Jews in Amsterdam and London to develop a new syncretic religion, which would merge Christian, Jewish, and Muslim mystical themes,” Rose and Hjern write. “This rather bizarre and secretive project had significant political ramifications in Sweden, Denmark, and Europe.” Swedenborg’s writings exerted a profound influence on the formation of esoteric “Illuminist” Freemasonry. They also shaped the popular literary and religious imaginarium of the cosmos in the United States during the 19th century. That is, Americans learned how to imagine the physical universe as a spiritual domain from Emanuel Swedenborg.

He “maintains that there is life on every planetlike body, including the moon that orbits our earth,” Rose and Hjern explain, for “to believe anything else would be to underestimate the divine love. Given the Lord’s primary goal of a heaven from the human race, why else, he argues, would planets exist except to support human beings and ultimately populate heaven?” For heaven was a physical place, Swedenborg reported. Why, it was right up there in the physical heavens! In fact, every world in the universe had its own heaven in heaven, all of them teeming with souls. He knew because he had talked to them, Swedenborg wrote. The souls of aliens had shared mental images of their worlds, and he had also traveled to visit their worlds, been allowed glimpses of their lives and afterlives, both heavens and hells.

“In all of his discussion of other planets, Swedenborg’s central point is clear: he aims to show that the worship of the Lord is not simply an Earth-centered religion. Jesus Christ is God of the entire universe.” Swedenborg intended his ecumenical and theosophical ideas to revive religion in the early modern world. Despite his far-seeing powers, however, Swedenborg could not foretell that the aliens would show up one day in flying saucers, or that it would happen in the New World.

Swedenborg was a scientific man as that term was understood in the 18th century, being a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and author of “a comprehensive three-volume work on natural philosophy and metallurgy” that made him famous in 1734. Thereafter, Swedenborg developed “a study of anatomy in search of the interface between the soul and body, making several significant discoveries in physiology,” Schuchard writes. He developed a theory that the universe and the human body contained mystical connections. In 1743, when he experienced his first visitation, Jesus Christ appeared and “called him to a new mission, and opened his perception to a permanent dual consciousness of this life and the life after death.” Thereafter, he could sense both the real and spiritual worlds at once, confirming his theories.

Swedenborg spent the remainder of his life writing “eighteen separate and quite distinctive works in twenty-five quarto volumes totaling about three and a half million words,” Rose and Hjern write. Swedenborg believed this literary mission was a divinely-appointed revelation for mankind. He wrote of the natural world as well as the spiritual world, which surely existed, he said, because he had been there to see it. He had also seen other planets, Swedenborg said, and this proved that heaven exists, for heaven “could not exist at all if it did not consist of people from a great many different planets.” Thus the universe itself was proof of God’s existence. For “if people consider how incredibly vast the starry heaven is and how incalculably huge the number of stars in it is — and each star is a sun in its own realm, has its own solar system, and is much like our sun, though it may vary from it in magnitude — they can come to believe there is more than one inhabited world in the universe.”

Ufology today makes this same argument all the time, though it is usually stripped of spirituality for broader public presentation and couched in the so-called Fermi paradox using arbitrary numbers. The median UFO or alien contact or abduction believer almost never begins their testimony with experiences of God or divinity. Instead, belief is presented as an experience, with spiritual implications flowing from whatever proof is presented for the experience, along with an argument that the sheer size of the universe is proof that the experience is real, or at least possible. “The only conclusion rational individuals can draw from this is that a means so vast for a purpose so great was not brought into being so that a single planet could then produce the human race and the heaven it populates,” Swedenborg says in a passage that could stand in for almost all Ufologists alive today. Surely God is far more ambitious than one little planet? “How would that satisfy the Divine, which is infinite, for which thousands or even millions of planets full of people would amount to so little a thing as to be almost nothing?”

The universe proves that God exists, which proves that heaven exists, which explains the purpose of the universe, which proves that God exists. “He rules the whole heaven and therefore also rules the whole world; whoever rules heaven also rules the world because the world is ruled through heaven.” It was circular logic, therefore foolproof, so that only a fool could possibly fail to agree. “Anyone who thinks with even slightly enlightened reason can conclude that creation came about so that heaven could arise from humankind.” Thus the universe and humanity were inextricably linked, and “any sensory function that is spiritual occurs in heaven, while any sensory function that is earthly occurs underneath heaven.”

As above, so below, as below, so above: this is the calling-card of Hermeticism and the occult, the influence of the alchemists and Joachim de Fiore and Jakob Böhme. Swedenborg thus belongs to the Age of Enlightenment and the rationalist thinkers influenced by early modern religious ideas which “played a hitherto unappreciated role in the formation of of the central ideas and ambitions of modern philosophy and science, particularly the modern project of the progressive scientific investigation and technological mastery of nature.”3 Swedenborg was an influence on Johann Wolfgang von Göethe and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, and through them, Hegel.

'Why Is Everyone Talking About Hegel?': James Lindsay and the New Critics of Utopia

They will try to blame James Lindsay. Who, to be clear, deserves credit for first-rate scholarship and being the first to popularize the knowledge he had gained. But the truth about Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and his intellectual heirs has always been out there, just waiting for someone to shine a bright light on it and call out loud until people noticed. James Lindsay is simply the man who did what was bound to be done, one day.

In 1758, Swedenborg republished the off-planet passages from his most famous work, Secrets of Heaven, in a new volume titled The Earthlike Bodies Called Planets in Our Solar System and in Deep Space, Their Inhabitants, and the Spirits and Angels There Drawn from Things Heard and Seen. Swedenborg afficianados refer to the book as Earths in the Universe, but its most popular name is simply Other Planets. All his work is organized in verses, like scripture.

Rather than exciting adventures, Swedenborg’s astral travels are dull, morally instructive visitations. “If we believe, as everyone should, that the Divine created the universe for the sole purpose of bringing humankind into being as the source of heaven (because humankind is the seedbed of heaven), then we cannot help but believe that wherever there is a planet there must be people on it,” he writes, and so we are to draw moral lessons from the existence of planets.

Swedenborg was eager to meet the aliens and learn their ways. “With some of them I spent all day, with others a full week, and with still others months on end,” he claims. “I learned from them about the planets they came from and are close to now, about the life, customs, and worship of the inhabitants of those planets, and various other noteworthy details about them.”

Because all communication was spiritual — the alien spirits read him “like a book” — there was never a language barrier, nor any cultural translation problem in his descriptions of societies and politics on other planets. Still, the interactions had a physical component. “I noticed that when they were communicating with me my own lips would move and my tongue would also move a little.” Once, when someone from Mercury came to visit him on earth, Swedenborg declined to read something aloud, and the refusal caused a sudden headache, “a painful kind of pressure on the right side of my head, from the crown to the ear.” Some aliens find their “spiritual auras” conflict with the auras of humans who are too materialistic. Earthly conflict repelled them. “When I tried to tell [residents of Jupiter] that in our world there are wars and robberies and murders, they turned away and did not want to hear it.”

The residents of Mercury “disregard bodily and earthly matters.” They read his mind to see his memories of places. While they are searching his memories, they concentrate on “what I knew had happened in those locations, as well as what form of government existed there, and what the character and customs of the citizens were, and things like that.” For “they found pleasure only in looking at what is real,” by which Swedenborg meant spiritual, “and none in looking at material, physical, or earthly things. This gave me confirmation that in the universal human the spirits from that planet relate to the memory of things that are apart from what is physical and earthly.”

These encounters could be complicated by the restless spirits of naughty earth humans. When Swedenborg read Jupiter spirits “passages from the Word about our Savior’s suffering on the cross, some European spirits put up horrifying roadblocks in order to steer the spirits from Jupiter away from belief.” Earthly enemies were creating this interference. “I asked who these European spirits were and what they had done in the world. I discovered that some of them had been preachers and many had been Jesuits, that is, members of the Society of the Lord.”

Swedenborg wrote in answer to the nascent atheism and skepticism of the 17th century. There were “many in the present-day church [who] do not believe in life after death and scarcely believe that heaven exists or that the Lord is the God of heaven and earth,” and in fact they were why God had opened “the deeper levels of my spirit,” Swedenborg writes. With his doors of perception open, “even while I am in my body I can at the same time be in the company of angels in heaven and not only talk with them but also see amazing things there and describe them.”

Swedenborg provides only a few vague details of alien life, however. Jupiter natives “said that on their planet they eat fruit from trees, and especially a kind of round fruit that grows out of their soil; they also eat vegetables. They wear clothes that they make from the fibers of the bark of particular trees that can be woven and also glued together with a kind of adhesive that they have.” This is subpar reporting.

Venus becomes the scene of a Platonic contest between “two kinds of people” being “of quite opposite dispositions.” One tribe (the thesis) is “gentle and humane” while the other tribe (the antithesis) consists of “people who are savage and almost feral.” The blood-tribe takes “great delight in pillage, and the greatest delight in eating plundered food. The pleasure they feel when they think about eating plundered food was communicated to me; I could tell that it was their supreme joy.” Swedenborg published these words in the middle of the Seven Years’ War that was ravaging Europe.

“Because this is what they are like, when they come into the other life they are completely overcome with evil and falsity,” Swedenborg says of the evil Venusians. The universe is vast, and filled with demons as well as angels. Existence is a synthesis of material and immaterial, good and evil, an esoteric construction. This is gnosticism, and in fact Swedenborg was an important inspiration to Protestant historian Jacques Matter (1791-1864), the first of the 19th century German gnostics.4 Matter used the words “gnosis” and “esotericism” interchangeably. So did his intellectual heirs, and so the terms became synonymous in modern religion.

Swedenborg’s Other Planets was intended for readers on earth. Earth was the scene of the Neo-Platonic thesis-antithesis-synthesis in Swedenborg’s work. “God chose to be born on this earth because, unlike other planets, the Earth has sustained written languages and global commerce for thousands of years,” he explained. Aliens had no writing of their own. “God was also born here because this earth is spiritually the lowest and outermost planet, and by coming from the highest to the lowest point he would bridge all points in between” — as above, so below, etc.

Strangely, his spiritual vision could only see what his naked eyes saw in the solar system. Swedenborg encounters alien spirits from Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the moon. None of them mentions Uranus, a planet discovered in 1781, nearly a decade after his death. The Mercurians’ description of their world bears no similarity to the sun-blasted rock revealed by multiple earth probes in the 20th century. Unaware of the earth atmosphere’s limits, or its effects on light, Swedenborg asserts that the stars “twinkle because of their fire.” Indeed, the discussion of alien atmospheres seems rather an opportunity for Swedenborg to show off his very limited understanding of the emerging science of earth weather.

They went on to say that that their climate was moderate, not too hot or too cold. It occurred to them to add that the Lord saw to it that their planet should not be too hot for them even though it was nearer the Sun than others, since the heat we feel depends not on our proximity to the Sun but on the depth and therefore the density of the atmosphere where we are, as we can see from the coolness felt on high mountains even in places where the climate at lower altitudes is hot. There is also the fact that the temperature varies with the angle of incidence of the Sun’s rays, as we can see from the seasons of summer and winter that each region goes through.

Swedenborg also visits five extrasolar planets. Swedenborg did not use a flying saucer or warp drive to tour the galaxy, of course, since no one had imagined such things yet. Instead, “spaces, distances, and consequently movement from place to place in the spiritual world are, in their origins and first causes, inner changes of state.” The heart is a hyperdrive. Furthermore, “to angels and spirits, these spaces, distances, and movements appear in accordance with those inner changes.” Thus, astral travel outside the solar system conveniently took only hours or days of time on earth.

How William Lilly Rationalized the Restoration

Like the best frauds, the inventor of modern astrology often started his pitches by calling out his critics and rivals in the art of confidence to make himself seem the more reliable informant. In the opening of his pamphlet on monarchy in 1660, for example, William Lilly warns readers of a “Spirit-Mongring Mountebank-Quack” who “cheated

During that time outside the solar system, Swedenborg observed “multiple meadows, deciduous forests, and woolly sheep” on one unnamed world. He does not include directions on how to get there. Having visited heaven and hell in his much longer work, Heaven and Hell, Swedenborg “was shown the hell for people from that planet. The people there were absolutely terrifying. I dare not describe their monstrous faces. I also saw women there who practice malignant sorcery. They appeared in green clothing and filled me with a sudden horror.” His descriptions of the spirit-world are fuller and livelier than the physical, material worlds he visits.

The aliens that he observes are also entirely human. He describes “some men” whose “faces were the same color as the skin of [Europeans] on our planet, but with the difference that the lower part of their faces was black rather than bearded and their noses were more snow-white than flesh-toned.” The aliens are Star Trek extras in makeup. All spirits, human and alien, are human-appearing, since “we come into the other life immediately after death and then look like people, with faces, bodies, arms, legs, and all our outer and inner senses,” even “wear clothes and have houses and homes.” Mars inhabitants see spirits from other worlds as “inhabitants of their planet” and cannot distinguish them as aliens until they “suddenly vanish from their sight.” Life with ghosts, what fun.

“I told them that something like this happened on our planet in early times, to Abraham, for example, Sarah, Lot, the inhabitants of Sodom, Manoah and his wife, Joshua, Mary, Elizabeth, and the prophets in general,” Swedenborg writes. Here, he prefigures the 19th century world of pseudohistory and the 20th century advent of Ancient Aliens he helped inspire. “I said that the Lord looked like other people and that the people who saw him could not tell that he was not just another earthly individual until he revealed himself.” God is an alien. Angels are aliens. “To the ancients as well, as is described in the Word, angels looked like people.”

In fact, through the pseudoscience of pre-Darwinian evolutionary ideas, Swedenborg has developed a hot new take on original sin: human beings are fallen aliens, which he can prove because ‘science,’ as he understood it, understood in his day that humans had developed the power of speech rather than having it from the moment of their creation.

“As should be clear to everyone, the earliest people could not have had verbal speech, because the words of a language are not instilled directly but must be invented and associated with things, something that can happen only with the passage of time,” Swedenborg insists. Before humans invented words for everything, they communicated only with their minds, for “this kind of speech was compatible with the speech of angels; it allowed the people of those times to be in actual communication with angels.” Nonverbal communication is superior to speech, for “when our face speaks or our mind speaks through our face, that is angelic speech in its outermost earthly form. This is not the case when our mouth is communicating verbally.”

Everything went wrong when humans started speaking words, Swedenborg says. “Because of this change in our state, heaven began moving farther and farther away from us; and this has continued to the present age, when people are no longer sure whether there is a heaven or a hell, and some even flatly deny that they exist.” As in heaven, “innocence reigned supreme then, accompanied by wisdom. Everyone did what was good because it was good, and what was upright because it was upright.” Then “as soon as the mind began to think one thing and say another (which happened when we began to love ourselves and not our neighbor) verbal speech began to gain ground, and the face became either silent or deceptive.” Restoring this as above-so below balance is the objective of all modern pseudoscience.

The fact that all aliens are capable of telepathic contact proved Swedenborg was right. “On all other planets, divine truth is revealed directly by spirits and angels,” Swedenborg explains, but because of this fall from our previous state, humanity must take instruction from those who are divinely inspired, such as himself, or Jesus.

He is primarily concerned with the transmigration of souls, not just in this world but also in the astral spirit-dimension. All flesh is mortal but the spirit is eternal. “The bodies we carry around in this world simply enable us to function in this earthly or terrestrial realm, which is the outermost one,” Swedenborg writes. Martians, on the other hand, “know that they will go on living after death, so they attach little importance to their bodies — only as much as is necessary for living, which they call continuing to serve the Lord. For the same reason, too, they do not bury the bodies of their dead but discard them and cover them with tree branches from the forest.”

Swedenborg “presents each gender as fully human, because each has will and intellect,” Rose and Hjern write. “In one presentation, the essential distinction between female and male is that will or volition predominates in women and intellect or discernment in men, which gives the genders different abilities and forms of wisdom.” This is an astrology of sex.

Swedenborg takes time in Other Worlds to defend the institution of monogamous marriage as a law of the universe. “Although Swedenborg’s work on marriage implies that every cell of the female is female and every cell of the male is male, his works generally emphasize the differences between male and female much less than their similarities, in that his theology is usually expressed in universal terms and concerns both sexes equally.” Equality is a divine plan for all creation. This was a rather challenging idea at the time, though it has proven too conservative for radicals.

Other Worlds is only one, rather short, work in a vast spiritual opus. Swedenborg clearly intended it to be one of many proofs of his Heaven and Hell rather than the centerpiece of his grander vision. Other parts of his ouvre were also better-read than others. His theosophical works won great fame, but his “eroticized spirituality and visionary meditation” earned “both fame and infamy,” Schuchard writes, inspiring their own imitators.

Among the many luminary creatives inspired by Swedenborg was English painter, printer, and poet William Blake, the subject of Why Mrs. Blake Cried: William Blake and the Sexual Basis of Spiritual Vision by Schuchard. Of course, “cried” in the title refers to an orgasm. Sexuality has always achieved a measure of acceptability through spirituality. Today, so-called Queer Theory frequently wraps itself in neo-Hermetic spirituality. Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble is also only intelligible as a neo-Gnostic bible. To oversimplifly the difference, an Hermetic construction is a gnostic construction with a positive (“progressive”) outcome, the basic building block of modern utopianism.

Swedenborg’s risqué prose also inspired the French writer Honoré de Balzac. Published in 1834, his novel Séraphîta makes a plot device of Swedenborg’s doctrine. The story is framed as a mystical love triangle. The titular character is a perfect androgyne, indeed an angel about to exit earth-life forever. To Minna, a woman, he is Seraphitus, who “judging by the pride on his brow and the lightning in his eyes seemed a youth of about seventeen years of age.” To Wilfred, she is Seraphita, who reassures him that “every woman from the days of Eve does good and evil knowingly.” Seraphitus/Seraphita wants Minna and Wilfred to marry each other and be happy, but both are smitten instead with the androgynous, angelic being before them.

As parents to this superhuman being, Balzac invents a “Baron de Seraphitz” who “was an ardent disciple of the Swedish prophet” married to “the daughter of a London shoemaker, in whom … the life of Heaven shone, she having passed through all anterior trials.” This odd couple was beloved of the city of Jarvis. “Their lives were those of saints whose virtues are the glory of the Roman Church,” a helpful pastor assures the reader. Their child was a holy miracle. “The day on which Seraphita came into the world Swedenborg appeared in Jarvis, and filled the room of the new-born child with light. I was told that he said, ‘The work is accomplished; the Heavens rejoice!’” Mere vessels of spirit, then “they prepared to bid the earth farewell; for they told me they should be transformed when their child had passed the state of infancy which needed their fostering care until the strength to exist alone should be given to her.” Thus abandoned as a child, Seraphita/Seraphitus naturally has attachment issues with humanity.

“Who art thou?” Minna asks in the opening scene, “with a feeling of gentle terror. ‘Ah, but I know! thou art my life. How canst thou look into that gulf and not die?’ she added presently.” They are cross-country skiing, with Seraphitus occasionally lifting Minna over obstacles with uncanny strength and dexterity, and they have stopped to gaze into a grand fjord. “Seraphitus left her clinging to the granite rock and placed himself at the edge of the narrow platform on which they stood, whence his eyes plunged to the depths of the fiord, defying its dazzling invitation. His body did not tremble, his brow was white and calm as that of a marble statue,—an abyss facing an abyss.”

“Seraphitus! dost thou not love me? come back!” she cried. “Thy danger renews my terror. Who art thou to have such superhuman power at thy age?” she asked as she felt his arms inclosing her once more.

“But, Minna,” answered Seraphitus, “you look fearlessly at greater spaces farther than that.”

Then with raised finger, this strange being pointed upward to the blue dome, which parting clouds left clear above their heads, where stars could be seen in open day by virtue of atmospheric laws as yet unstudied.

“But what a difference!” she answered smiling.

“You are right,” he said; “we are born to stretch upward to the skies. Our native land, like the face of a mother, cannot terrify her children.”

His voice vibrated through the being of his companion, who made no reply.

After one more scene set before a yawning fjord, the melancholy angel-being leaves earth, inspiring great sadness, and the human couple becomes a “celestial couple.” Angels appear. “Wilfrid and Minna saw neither their coming nor their going; they appeared suddenly in the Infinite and filled it with their presence, as the stars shine in the invisible ether.” Then: “A mighty movement was perceptible, as though whole planets, purified, were rising in dazzling light to become Eternal.”

Seraphita/Seraphitus is a metaphor for God and Jesus, transcending the original sin of humanity at birth, calling on other humans to replicate its creation by imitating its creators. Creation, here, requires a physical and metaphorical death. However, modern gnosticism has brought plenty of literal death.

De Balzac anticipates the genderless androgyny of modern gnostic religions seeking to overthrow their evolved humanity, especially their sex. “Man himself is not a finished creation; if he were, God would not Be” anticipates the latter-day Hermeticism of transhumanist ideology. Terasem, a transhumanist religion founded by transgender billionaire Martine Rothblatt, holds as an article of faith that “nanotechnology and related cyber consciousness” are capable of “relieving human suffering and extending human life,” i.e. technology can defeat pain and death. Man can invent God by reinventing humanity, even reinventing himself as a woman. Thus feminized, humanity is supposed to be more peaceful, cooperative, evolved.

Riding A Comet Through Heaven's Gate

During the afternoon of 26 March 1997, San Diego sheriff’s deputies responding to a 911 call discovered 39 bodies decomposing at a residence in the suburb of Rancho Santa Fe, California. The dead wore black uniforms: Nike Decades sneakers, sweat pants, and shirts with patches reading “Heaven’s Gate Away Team.” Purple shrouds covered their faces. Everyone had $5.75, a five dollar bill and three quarters, in their shirt pocket.

Of course, de Balzac was a French Catholic reacting to Swedenborg’s Protestant writings long before nanotechnology was possible, or even imaginable. Like Swedenborg, de Balzac enjoys the early benefits of scientific method, which was still evolving away from pseudoscience, while rejecting a godless creation. “Men ever mislead themselves in science by not perceiving that all things on their globe are related and co-ordinated to the general evolution, to a constant movement and production which bring with them, necessarily, both advancement and an End,” de Balzac writes. His book was published in the very middle of the reign of Louis Philippe I, penultimate king of France. Louis Philippe had to contain the contradiction of Revolution and Restoration, abdicating fourteen years after the book’s publication, when the changes wrought by industrial revolution had made it impossible to contain the contradiction of progress and tradition anymore.

Despite the upheavals of state, France was an empire in the 19th century, as Europeans raced to claim the last bits of the planet for colonies. Empire always brought the newly-contacted culture back to its own metropole, so Europeans were continually reacting to non-European spirituality. “The fantastic literature of the East offers nothing that can give an idea of [Swedenborg’s] astounding work, full of the essence of poetry, if it is permissible to compare a work of faith with one of oriental fancy,” de Balzac writes. Chauvinism gave way to fascination, however.

With the world shrinking to a unity in metaphorical terms, the moment had come for men to discover new worlds on new planets. Swedenborg had created the imaginarium for doing so.

Swedenborg’s “journeys through the Astral Regions” impress de Balzac, for “his descriptions cannot fail to astonish the reader, partly through the crudity of their details. A man whose scientific eminence is incontestable, and who united in his own person powers of conception, will, and imagination, would surely have invented better if he had invented at all.” Colin Bennett makes the same excuse for George Adamski, the world’s first UFO “contactee,” in his book Looking for Orthon. The Seekers, a Chicago area UFO cult that became famous for predicting the end of the world in 1954, also believed that nothing meant something, that failures of prophecy were simply prophecies of spiritual events they had misunderstood to be literal prophecies. Faith does not argue from verisimilitude, or realism. Faith argues from belief and adapts disconfirming information unto itself.

Indeed, de Balzac uses the legend of Swedenborg as an inspired truth within his fiction. “The transportation of Swedenborg by the Angel who served as guide to this first journey … is among the oral traditions left by Swedenborg to the three disciples who were nearest to his heart,” he writes with the assurance of devout Muslims that Muhammad did really visit heaven on his Night Journey. “Monsieur Silverichm has written them down,” de Balzac writes, invoking the kabbalists. “Monsieur Seraphitus endeavored more than once to talk to me about them; but the recollection of his cousin’s words was so burning a memory that he always stopped short at the first sentence and became lost in a revery from which I could not rouse him,” one of de Balzac’s characters says. Believed by some Swedenborgians even to this day, this tale has all the substance and evidentiary basis of a hadith.

The spiritual encounter of east and west also took place in the United States, specifically western New York, a region known as the “burned-over district” for its frequent religious revivals. Joseph Smith promulgated a new religion there in 1820. It started with a vision, or theophany, in the woods that Latter Day Saints call the Sacred Grove. Over time, and with several movements around and across the young country, his revelation developed into the Church of Latter Day Saints. That development process is controversial, most of all the question of Smith’s sources and influences. To say that Smith was inspired by another person’s writing is to challenge the divine source of his inspiration. As we have repeatedly observed in this essay series, however, all religions in the modern world are bricolages, that is, pastiches of cultural materials the believer has found in their environment, all glued together by belief, and always layered on top of some ancient spiritual canvas. Smith revealed an explicit sequel to the bible, as well as an expanded universe of bible-ish lore that encompassed the North American continent. As the first religion born in the new United States, Mormonism had to explain the United States.

In a critical essay examining the evidence for Swedenborg’s influence on Smith, Mormon historian J.B. Haws admits there are four connections of varying quality.

First, the Prophet apparently mentioned Swedenborg by name during an 1839 conversation with Edward Hunter, a student of Swedenborg-ianism who later became a Latter-day Saint. Hunter had established a seminary dedicated to the free exchange of religious ideas, and when Joseph Smith stopped at this Nantmeal Seminary in Pennsylvania during a return trip from Washington DC, Hunter reported this exchange: “I asked him if he was acquainted with the Sweadenburgers. His answer I verially believe. ‘Emanuel Sweadenburg had a view of the world to come but for daily food he perished.’” If accurately remembered, this remark generates a whole range of questions.

Second, because both men described a heaven that consisted of specific and separate realms, there seems to be a greater qualitative correspondence in their respective views than in the more nebulous “many mansions”–type descriptions of heaven found in the writings of other contemporary theologians. McDannell and Lang “trace the roots of the modern heaven, at least in part, to Swedenborg” and see echoes of that “modern heaven” in Mormonism.

‘Modern heaven,’ according to Swedenborg, was divided into three parts, each hosting different grades of soul, with a “celestial heaven” at the top. Even within heaven, souls still transmigrated, advanced, and progressed. It was a popular idea in the so-called New Church, the cluster of Christian reformist movements that Swedenborg inspired. Johnathan Chapman, known as Johnny Appleseed, was perhaps his most prolific New World missionary. By the time Joseph Smith revealed his divine message, Swedenborg — and his belief in life on other planets — were as American as apple pie. Smith’s remark, “but for daily food he perished,” simply refers to the utter rejection of materialism in Swedenborg’s work.

As Haws explains, Smith likely did encounter Swedenborg through a “Mormon convert, Sarah Cleveland, and her Swedenborgian husband, John Cleveland” during an 1839 sojourn in Quincy, Illinois, prior to his recorded remark about Swedenborg. Yet this does not explain why Smith promulgated his three-layered heaven seven years earlier. Instead, Hows notes, historian Michael Quinn has established that Swedenborg’s translated books and pamphlets were available around Palmyra, New York, where Smith lived when he received his first revelation. Lucy Mack Smith has likewise established that Sidney Rigdon, one of the earliest Mormon leaders and Smith’s principal scribe, was also exposed to Swedenborg before he ever met Joseph Smith. Haws finds this to be the clearest and most fascinating connection between the founding ideas of Mormonism and the ideas of Swedenborg.

Smith dictated part of The Book of Abraham in 1835. The rest was composed some time before publication in 1842, after Smith bought four papyrus scrolls that had accompanied an exhibition of Egyptian mummies. Now identified as mere funerary prayers, standard ritual items associated with burial of the dead in ancient Egypt, the papyri contained for Smith a vision of Abraham, father of the Abrahamic faiths. His translation of the heiroglyphs remarked on a star “nearest to the throne of God” called Kolob. Sun, moon, and earth represented a heavenly hierarchy. Furthermore, one day on the planets circling Kolob lasted 1000 years on earth. This was Dispensationalism, and at the time, many fervent American Protestants — the first Dispensationalists — were convinced that Judgement Day was scheduled in 1844, just two years in the future when Smith published The Book of Abraham, because the final 1000-year Dispensational cycle had been fulfilled.

Mormon religion is therefore very accepting of ideas about extraterrestrial existence. We shall return to this topic in a future essay, for it bears on the ecumenical 21st century UFO religion. We need only cite here the example of the late Nevada Senator Harry Reid, whose friendship with another UFO-obsessed Mormon, Robert Bigelow, led eventually to the sensational hearing with David Grusch in 2023. Fitting the pattern of Ufology stripping off its religiosity in order to ‘pass’ as scientific, Grusch did not present his secondhand testimony as a spiritual endeavor, but has revealed himself as a spiritual leader since then — to almost no fanfare at all.

The Extraterrestrial Evangelism of David Grusch

David Grusch, who made headlines last summer by telling a congressional committee about secondhand reports of dead aliens and their spaceships being held in secret facilities, said in November that he wants those supposed secrets released in order to bring a “spiritual awakening” to the world.

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps “finds in the writings of Swedenborg much that is attractive,” Mary Angela Bennett writes in her 1939 biography.5 Phelps references “Professor George Bush, who wrote his Treatise on the Millennium in 1832 and in 1847 became a Swedenborgian,” as well as Swedenborg himself, at length, in her 1868 book Gates Ajar. The American Civil War had been over for three years and a nation in mourning yearned to hear that the gates of heaven were open to all.

Her story centers on Mary Cabot, who loses a brother, Roy, in a the war. Calvinist gatekeeping of the afterlife does not resolve her grief. A cousin, Winifred, convinces Mary that the gates of heaven are open to all, describing heaven as an all-American pastoral scene straight from Little House on the Prarie. It was the first of three novels Phelps wrote about Spiritualism, the second 19th century American religion inspired in part by Swedenborg. A pioneer of progressive causes, including campaigns against vivisection of animals and for the emancipation of women, Phelps became the first woman to lecture at Boston University in 1876. Feminism had arrived.

Phelps’s Swedenborgian view of heaven was pervasive by the end of the 19th century. Acknowledging reciept of a copy of Swedenborg’s Other Worlds in an 1891 letter, Mark Twain found it “charmingly written, and it interested me. But it flies too high for me. Its concretest things are filmy abstractions to me, and when I lay my grip on one of them and open my hand, I feel as embarrassed as I use to feel when I thought I had caught a fly.” He had noticed the perceptual weakness of Swedenborg’s observations. Mocking Swedenborg’s claims of mental transmission and Spiritualist ideas about “mental telegraphy,” Twain offered “to try to mail it back to you to-day — I mean I am going to charge my memory. Charging my memory is one of my chief industries.” It was an age of industrial revolution and electric lighting, when physicians were finally learning to be scientists, and telegraph cables brought news from around the world.

Bennett complains that “Mark Twain, in one of his too frequent lapses from sound judgment, wrote a travesty of The Gates Ajar not long after its publication. This was kept out of the periodicals of that day only by the restraining hand of Mrs. Clemens.” Twain scholars write that he in fact spent many years grappling with his story, which finally “appeared … in a modified form in Harper's for December 1907 and January 1908,” as Bennett notes. Seth Murray writes that Twain only finished the story after a 1907 encounter with Fabian Socialist George Bernard Shaw. The playwright Shaw read “a bit from what became his piece ‘Aerial Football: The New Game,’” which lampooned the expectations of heaven in a working class British woman. Twain, who was sympathetic to the women authors of his time, likewise “stages a series of surprises and disappointments of expectation” in his story to undermine the idea of nondiscriminatory afterlife. However, Twain’s story “did not start out that way,” Murray says.

Murray identifies “Extract from Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven” as a Menippean satire, which he defines as “a critique of mental attitudes and systems, rather than persons.” This literary subgenre is “generically characterized by its formal zaniness, its intellectual fervor, its excursion away from traditional norms of storytelling, and its comfort with essayistic digression into topics that would typically be shut out of novelistic representation,” Murray writes. “Basically, they are narratives that reflect genuine erudition and no reluctance about displaying it, paired with irreverence and iconoclasm, and that finally possess a willingness to talk about systems and structures and to then probe their failures.”

Furthermore, “Menippean satires are also characterized by loose plotting and very little of what looks like a chain of actions and conflicts that characterize a story—they are, for example, often left unfinished.” Stormfield is unfinished as a tale, for who could ever write a book containing eternity? Just look at Swedenborg, who tried, and wrote millions of words but still left out the planets Uranus and Neptune, the latter being discovered in 1848. Such were the temporal dangers of literary prophethood.

Twain’s story begins with the titular Captain Stormfield explaining to Saint Peter just why he has turned up at the wrong gate of heaven. He had been in no hurry, expecting “warm quarters,” but “when I had been dead about thirty years I begun to get a little anxious. Mind you, I had been whizzing through space all that time, like a comet. Like a comet!” Encountering “a most uncommonly big” comet, Stormfield elected to alter course and have a race. “In about a minute and a half I was fringed out with an electrical nimbus that flamed around for miles and miles and lit up all space like broad day,” Twain writes in a scene that deserves CGI animation. The comet, Stormfield says, was a demonic freighter bound for hell with a load of brimstone, which it also burned as coal. “I judged I had some reputation in space, and I calculated to keep it,” Stormfield tells Peter.

There was “a power of excitement on board the comet.”

Upwards of a hundred billion passengers swarmed up from below and rushed to the side and begun to bet on the race. Of course this careened her and damaged her speed. My, but wasn’t the mate mad! He jumped at that crowd, with his trumpet in his hand, and sung out—

“Amidships! amidships, you—! or I’ll brain the last idiot of you!”

When Stormfield teases the demonic captain of this comet-steamship, it accelerates again with “such another powwow — thousands of bo’s’n’s whistles screaming at once, and a crew like the populations of a hundred thousand worlds like ours all swearing at once. Well, I never heard the like of it before.”

Having gone off course for his assigned heavenly gate in order to enjoy this race on what he presumes to be his trip to hell, Stormfield comes upon “gates, miles high, made all of flashing jewels, and they pierced a wall of solid gold that you couldn’t see the top of, nor yet the end of, in either direction.” Arriving at the wrong gate, he “noticed that the skies were black with millions of people, pointed for those gates. What a roar they made, rushing through the air! The ground was as thick as ants with people, too — billions of them, I judge.”

Confused by the heavenly clerk’s questions about his origins, Stormfield identifies himself first as a San Franciscan, then as an American, and finally as a resident of “the world.” Only when the clerk asks him to step aside does Stormfield realize that he is surrounded by people from some other planet, for “a sky-blue man with seven heads and only one leg hopped into my place.” Trying again, Stormfield tells the clerk that his home planet is “the one the Saviour saved.”

He bent his head at the Name. Then he says, gently —

“The worlds He has saved are like to the gates of heaven in number — none can count them. What astronomical system is your world in? — perhaps that may assist.”

“It’s the one that has the sun in it — and the moon — and Mars” — he shook his head at each name — hadn’t ever heard of them, you see — “and Neptune — and Uranus— and Jupiter —”

This last clue leads to discovery. Only after admitting that he has wandered off-course by racing a demonic comet-steamship does Stormfield eventually learn that his home planet is called “the Wart.” Furthermore, the clerks do not immediately equip Stormfield with “my harp, and my wreath, and my halo, and my hymn-book, and my palm branch,” for they do not know “the varied customs of the countless kingdoms of heaven.”

It makes my head ache to think of it. I know the customs that prevail in those portions inhabited by peoples that are appointed to enter by my own gate — and hark ye, that is quite enough knowledge for one individual to try to pack into his head in the thirty-seven millions of years I have devoted night and day to that study. But the idea of learning the customs of the whole appalling expanse of heaven — O man, how insanely you talk!

Finally, Stormfield is directed to a red carpet that will teleport him to the correct heaven, which he finally understands to be his own personal heaven. His arrival echoes Ellis Island: he is in fact an immigrant to a new land. For as Stormfield learns, “this Heaven ain’t built on any ‘Gates Ajar’ proportions.”

To the contrary, “the main charm of heaven — there’s all kinds here —which wouldn’t be the case if you let the preachers tell it” is that everyone segregates their fellow heavenly beings into a personal heaven. “Anybody can find the sort he prefers, here, and he just lets the others alone, and they let him alone. When the Deity builds a heaven, it is built right, and on a liberal plan,” a Sandy McWilliams “from somewhere in New Jersey” tells Stormfield.

He encounters “Yanks and Mexicans and English and Arabs” as well as a “Pi Ute Indian” who died of cannibalism. So diverse is heaven that non-earth angels who even know about Stormfield’s origin-planet think that white and black Americans are “Injuns that have been bleached out or blackened by some leprous disease or other — for some peculiarly rascally sin, mind you.”

“Old man, I’ll be frank with you,” Stormfield confesses to Sam. “This ain’t just as near my idea of bliss as I thought it was going to be, when I used to go to church.” By this point, he has ditched the halo and wings, which turn out to part of the military uniform angels wear on important occasions rather than everyday garb in heaven. “Eternal Rest sounds comforting in the pulpit, too,” Sam replies. “Well, you try it once, and see how heavy time will hang on your hands. Why, Stormfield, a man like you, that had been active and stirring all his life, would go mad in six months in a heaven where he hadn’t anything to do. Heaven is the very last place to come to rest in, — and don’t you be afraid to bet on that!”

People still work in heaven, earning their keep, because real happiness lies in overcoming challenges. For “happiness ain’t a thing in itself—it’s only a contrast with something that ain’t pleasant … As soon as the novelty is over and the force of the contrast is dulled, it ain’t happiness any longer, and you’ve got to get up something fresh. Well, there’s plenty of pain and suffering in heaven—consequently there’s plenty of contrasts, and just no end of happiness.”

Heaven is not an egalitarian republic, Stormfield learns. “There are ranks, here. There are viceroys, princes, governors, sub-governors, sub-sub-governors, and a hundred orders of nobility, grading along down from grand-ducal archangels, stage by stage, till the general level is struck, where there ain’t any titles,” Sandy explains. Moreover, everyone in heaven is given their “rightful rank,” so that “Shakespeare and the rest have to walk behind a common tailor from Tennessee, by the name of Billings; and behind a horse-doctor named Sakka, from Afghanistan. Jeremiah, and Billings and Buddha walk together, side by side, right behind a crowd from planets not in our astronomy; next come a dozen or two from Jupiter and other worlds; next come Daniel, and Sakka and Confucius; next a lot from systems outside of ours; next come Ezekiel, and Mahomet, Zoroaster, and a knife-grinder from ancient Egypt; then there is a long string, and after them, away down toward the bottom, come Shakespeare and Homer, and a shoemaker named Marais, from the back settlements of France.”

Nor can heaven provide perfect contentment for everyone all the time, since humans still have free will in heaven. Stormfield is shown a weeping cranberry farmer who, having lost a child, “kept that child in her head just the same as it was when she jounced it in her arms a little chubby thing. But here it didn’t elect to stay a child.”

No, it elected to grow up, which it did. And in these twenty-seven years it has learned all the deep scientific learning there is to learn, and is studying and studying and learning and learning more and more, all the time, and don’t give a damn for anything but learning; just learning, and discussing gigantic problems with people like herself.

The story is imbued with Twain’s own “vexed relationship to God,” Murray writes, placing him in the 19th century category of “sentimental literature.” However, Twain was clearly satirizing a popular cosmology, that is, a widespread belief about the spiritual nature of the cosmos, that Swedenborg had inspired in Americans.

Twain’s satire risked offending innumerable readers, not just his wife. Like The War Prayer, which Twain famously declared could be published only after his death, “Stormfield” simply waited until he felt the end was coming. Indeed, in 1909 he said he would ride out on Halley’s comet the following year. “The Almighty has said, no doubt, ‘Now there are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together,’” Lapham’s Quarterly chronicles Twain remarking, adding: “He died on April 21, 1910—one day after the comet had once again reached its perihelion.”

Once again, western New York, home of the New Church, had hosted a religious revival in the Spiritualist movement, which had used Swedenborg as a source inspiration. Religious freedom also beckoned the third, and final, spiritual actor in this essay to New York City. Helena Petrovna Hahn von Rottenstern, better-known as “Madame Blavatsky,” immigrated there from Russia in 1873 to found the Theosophical Society. Sharing all the same western esoteric influences as Swedenborg’s theosophical writings, such as Hermeticism and Neoplatonism, Blavatsky’s new church added a capital-T to the study of theosophy by importing Hinduism and Buddhism to America to serve as cultural canvas for her bricolage. The motto of her church, “There is no religion higher than truth,” conveniently allows the believer to override conflicting theological orthodoxies through the spiritual magic of divined truth, or as we say in the 21st century, lived experiences. In the spirit-world, or astral plane, it is of course much easier to have these sorts of magical experiences.

Blavatsky did commune with spirits of the dead, most famously in her séances that led to damaging accusations of fraud. However, she insisted that not all entities contacted through telepathy were dead, that some of them were alive, while still others were in fact Ascended Masters from earth offering enlightenment to those earthlings who communed with them. Moreover, these Ascended Masters lived on other planets in the solar system and beyond. The residents of our own solar system all knew of our existence, for “all such planets as Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, etc., etc., or our Earth, are as visible to us as our globe, probably, is to the inhabitants of the other planets, if any, because they are all on the same plane” of existence, according to Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy. She was reinventing Swedenborg with the eastern scriptures that Honoré de Balzac had dismissed in comparison to Swedenborg’s.

Blavatsky’s cosmology was hierarchical, for “the planets are not merely spheres, twinkling in Space, and made to shine for no purpose, but the domains of various beings with whom the profane are so far unacquainted; nevertheless, having a mysterious, unbroken, and powerful connection with men and globes,” Blavatsky writes. “Every heavenly body is the temple of a god, and these gods themselves are the temples of God, the Unknown ‘Not Spirit.’” This is an ancient Gnostic construction. “There is nothing profane in the Universe,” she adds, evoking the Hermetic understanding of the material world from which first alchemy, then science, emerged.

Blavatsky placed Lord Sanat Kumara, or Ādi-Śankara, a figure from Vajrayana Buddhism whom scholars believe to be at least partly myth, on Venus as one of the “Lords of the Flame.” No expert in the language of the text, Blavatsky clearly mistranslated The Stanzas of Dzyan, the Tibetan book from which she sourced her knowledge of Kumara. Historians now rubbish her claims to have visited Tibet before arriving in the United States. She did however visit the island of Ceylon in the Indian Ocean, now known as Sri Lanka, to establish the church of Theosophy in the subcontinent before she published The Secret Doctrine. Two more books followed before her death in 1891.

An entire essay in this series will be necessary to describe the transmission of Swedenborgianism to the 20th century. In summary, Annie Besant, whom Blavatsky appointed her spiritual heir, and Charles W. Leadbeater were fascinated by the scant reference to Kumara and his friends on Venus.

In their co-authored book Man: Whence, How and Whither, they write that “those known as the Lords of the Flame, who arrive from Venus on the fourth globe, in the fourth Round, in the middle of the third Root Race, quicken mental evolution, to found the Occult Hierarchy of the Earth and to take over the government of the globe” in the next Dispensational age, the Aquarian one. “It is They whose tremendous influence so quickened the germs of mental life that [religious faiths] burst into growth,” only to be ruined by orthodoxies.

The topic recurs in their Talks on the Path of Occultism. “Still, we must not forget if the Lords of the Flame from Venus had not left Their system and come down into ours to help us, we should at least be one round behind the position that we have so far achieved.” Horror writer H.P. Lovecraft was fascinated by Blavatsky and Theosophy, though not as a believer. His conception of the universe as uncaring, of the gods within it being older than earth or even the universe and unconcerned by the fate of humanity, can be seen as the literary photo-negative of Swedenborg’s Other Planets.

Remarking on the above passages of Blavatsky, Besant, and Leadbeater, the official website of the Church of Theosophy refutes any literal interpretation. “It is obvious that physical beings are not referred to here as it is utterly impossible for any sort of life as we know it to exist on the physical surface of Venus,” they write. But this was not in fact obvious to any of these writers at the time, and as we have established in this essay, Swedenborg had imbued American spirituality with literalist belief in life on other planets, both in the solar system and throughout the universe, from America’s conception as a nation.

Between the publication of Swedenborg’s Other Planets and the first worldwide headline UFO sighting by pilot Kenneth Arnold, 189 years of spiritual and literary reaction to Swedenborg took place. Like Emanuel Swedenborg writes in Other Planets, believers in extraterrestrial visitations of earth dismiss doubters as “people who at heart have already denied the reality of heaven and hell and life after death,” enemies of God who are “adamantly opposed to these descriptions and will deny them, because it is easier to make a crow white than it is to make people believe something once they have rejected faith from their heart.” Unbelief is explained as bad character. “This is because they constantly approach such matters from a negative perspective and not from an affirmative one,” Swedenborg says.

It is true if you believe it is true, because you believe it. You can trust me. So said all of them, throughout the 19th century, and so say they say now. The believer always stigmatizes unbelief. In our postmodern world, however, the latter-day Swedenborgian believer tends to shed their spirituality for public performances of the belief in extraterrestrial contact. We have already seen this pattern recur thoughout the UFO cults and we shall see more of it as we examine further modern examples. Emanuel Swedenborg is the bookend to the present day in our study, the leftmost limiter on the rightward-advancing timeline of explicitly extraterrestrial contact, showing that such phenomena have always been reported as spiritual and moral lesson.

In many examples we have studied, a war was current or recent, inspiring providentialism, and then a range of responses followed. The history of the idea of aliens in the heavens, and the modern history of the idea of angels in heaven — a modern heaven — is the same history.

Moreover, as an explicitly gnostic belief, UFO faith can piggyback on (some would say parasitize) any existing religion through the bricolage effect. Matt Walsh and Republican congressmen believe in flying saucers. Democratic Senator Harry Reid believed, and far-left stunt lawyer Daniel Sheehan still believes, in flying saucers. People of all faiths and descriptions believe in flying saucers. We are still living in the age of Swedenborgianism, which happened at the waypoint between “early modern” and “modern world.” There is nothing “New Age” about aliens from other worlds. ‘They’ have always been with us moderns, at least the ones who believe.

Unidentified Flying Archons: How A Global Religion Reinvented Itself For A 'New Age'

The term ‘New Age’ has always been a false conceit in reference to the 1970s, or any time in the 20th century. American Christianity beheld a world of spiritual ideas during the 19th century. Across the globe, including the United States, new religions were forming around universalizing ideas of humanity. Hegel and Marx presented new revelations to explain

Schuchard, Marsha Keith. Emanuel Swedenborg, Secret Agent on Earth and in Heaven: Jacobites, Jews and Freemasons in Early Modern Sweden. Brill, 2012.

Rose, Jonathan and Hjern, Ollie. Scribe of Heaven: Swedenborg's Life, Work, and Impact, Jonathan S. Rose, et al. editors, Swedenborg Foundation, Incorporated, 2005.

Magee, Glenn Alexander. Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition. Cornell University Press, 2001.

Faivre, Antoine. “‘Gnosis’ in Western Esoteric Movements.” The Gnostic World. Routledge, 2019.

Bennett, Mary Angela. Elizabeth Stuart Phelps. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1939.