Riding A Comet Through Heaven's Gate

Christianity, Theosophy, and the flying saucer apocalypse

During the afternoon of 26 March 1997, San Diego sheriff’s deputies responding to a 911 call discovered 39 bodies decomposing at a residence in the suburb of Rancho Santa Fe, California. The dead wore black uniforms: Nike Decades sneakers, sweat pants, and shirts with patches reading “Heaven’s Gate Away Team.” Purple shrouds covered their faces. Everyone had $5.75, a five dollar bill and three quarters, in their shirt pocket.

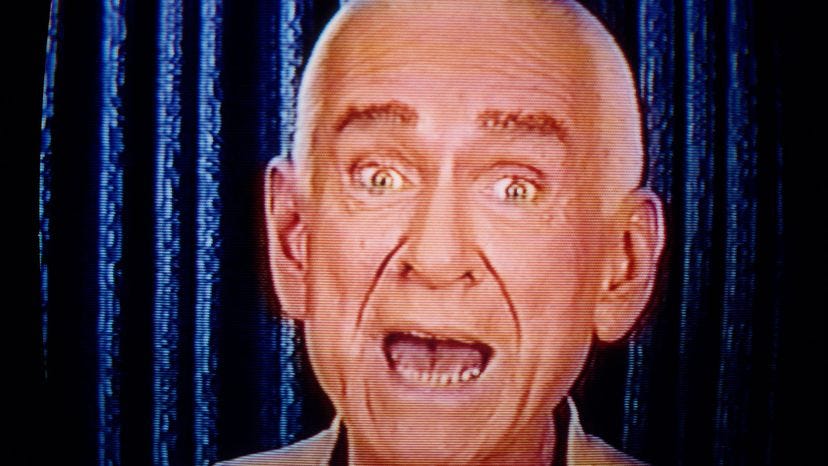

Heaven’s Gate was a tiny religious community, more colloquially called a ‘cult,’ and the phrase “away team” was just one of many Star Trek references they used as spiritual terminology. Adding a layer of uncanny surrealism, one of the dead members of the group was in fact Thomas Nichols, brother of actress Nichelle Nichols, who played the part of Uhura in the original Star Trek TV series. Researchers would determine later that at the beginning of his spiritual leadership, cult founder Marshall Herff Applewhite Jr. was at least partly inspired by the works of science fiction authors such as Robert Heinlein and Arthur C. Clarke. In Beyond Human—The Last Call, a series of satellite TV broadcasts by the cult in 1991-1992, Applewhite explained that science fiction language was one of the “contemporary ways to express our information that could potentially override traditional religious, as well as ‘New Age,’ preconceptions and stereotyping.” They thought it made them more normal-seeming.

The group was not kidding about their “Next Level Language.” They were becoming “Next Level Beings” with extraterrestrial bodies, therefore their shared house was a “craft,” and anyone who left the house was conducting “out of craft tasks.” According to Robert W. Balch, one of the first scholars to encounter Heaven’s Gate in its formative years, this was a cult practice from the beginning, wherever they abided. Within their “craft,” Heaven’s Gate had “rest chambers” rather than bedrooms, a “nutri-lab” instead of a kitchen, and an office they called “the compu-lab.” Early adopters of the internet, Heaven’s Gate made a fair income from building web pages in the first two years of the web. Someone even posted the group’s final website update from their compu-lab. “Our 22 years of classroom here on planet Earth is finally coming to conclusion,” they announced. This was their moment of “graduation” from being mere humans. They were leaving “this world” in order to “go with Ti’s crew” to the Next Level in a spaceship.

Ti was the cult name of Bonnie Nettles, longtime spiritual partner and Platonic companion to Applewhite, who went by Do. Nettles had died of metastatic cancer in 1985, leaving Applewhite to lead their little church on his own. He had planned to go with her on the spaceship, and so Applewhite’s theology shifted. Members first speculated that Applewhite was Jesus as early as 1975. It became church doctrine between 1992 and 1994. In 1994, Applewhite announced that Nettles (“Grandfather”) was God, and that the cult might have to give up their mortal forms in order to be with her again. The following year, Heaven’s Gate publicized themselves on Usenet with an explicit claim that Applewhite was Jesus (“Father”). He said the world was ending soon. He was waiting for a sign, he said, and at the end of 1996, the Hale-Bopp comet provided one.

Heaven’s Gate began to prepare for their rendezvous with Ti. They were certain the time had come, now, and that they knew what to expect, because they were avid listeners of AM talk radio star Art Bell. When the story of a planetary spaceship following the comet turned out to be a hoax, Applewhite and his little flock remained undeterred. Their belief that the world was about to be “recycled” was too strong for disconfirmation with evidence. While scholars have acknowledged that Bell’s program triggered a group that was well along its way to mass suicide, this essay might be the first attempt to understand exactly what the broadcast contained that resonated so strongly with Heaven’s Gate.

From the moment their bodies were discovered, a debate has raged over why the members of the group agreed to die together. Sociologist Janja Lalich has proposed an explanation in “Bounded Choice,” her own term for cult brainwashing, and describes their deaths as “murder.” Catherine Wessinger calls the mass suicide “violence.”

However, as Benjamin Zeller points out in Heaven's Gate: America's UFO Religion, ‘brainwashing’ doesn’t actually exist, and Heaven’s Gate did not engage in coercive control.1 Such theories cannot explain why so many people voluntarily took their own lives, nor why they became part of the group in the first place. “Members joined not because of some sort of magical psychological or spiritual trick that the leaders conjured, but because they were looking for something and believed that they found it in Heaven’s Gate,” Zeller writes. They died as they had lived, as they had believed, “evolving” beyond their humanity. Why, their new bodies in the extraterrestrial afterlife would even be plant-based instead of mammalian. Zeller:

The opinions of Robert W. Balch and David Taylor most closely match my own, and since they are the two sociologists with the longest-standing research background in the study of the group, their interpretation relies on the most support. “[T]he suicides resulted from a deliberate decision that was neither prompted by an external threat nor implemented through coercion. Members went to their deaths willingly, even enthusiastically, because suicide made sense to them in the context of a belief system that, with few modifications, dated back to Ti and Do’s initial revelations,” the two sociologists wrote in their 2002 analysis of the Heaven’s Gate suicides.

Wessinger notes that “of the thirty-eight followers” who died with Applewhite, “thirty had joined the group in the 1970s (although not all had remained with the group continuously), and eight had joined in the 1990s.”2 Nineteen men and twenty women, of ages ranging from members in their twenties to a woman in her seventies, shared nothing in common other than a belief and a monastic way of life.

A spiritual biography of the Heaven’s Gate cult reveals the familiar spiritual bricolage that this essay series on the history of UFO cults has identified in every example studied. Nettles and Applewhite/Bo and Peep /Ti and Do were “creative recyclers of cultural wares,” the definition of a brocoleur according to anthropologists Claude Lévi-Strauss and Wendy Doniger. They were Christians interested in alternative religion, appropriating forms and ideas from here and there, rejecting what did not seem right, changing their minds over time.

Nettles was raised as a Baptist, Applewhite as a Presbyterian. The core of their theology was a literalistic, even fundamentalist reading of the bible with an “extraterrestrial hermeneutic,” Zeller says. Their interpretation of scripture simply incorporated popular UFO beliefs. As Jesus was beamed aboard a flying saucer (the Transfiguration), so the “students” of “the class” would beam aboard a spaceship when they left their bodies on earth. As Jesus was physically resurrected into his pre-existing alien body, so the believers would inhabit prepared physical bodies when they, too reached The Evolutionary Level Above Human (TELAH). In the group’s ‘88 Update, Heaven’s Gate declared Jesus himself to be an alien-human hybrid. When Applewhite spoke of heaven, he meant a literal, physical heaven located up in the actual heavens, reachable by flying saucer.

Believers thus held a view of salvation (soteriology) consistent with “the Rapture,” but the cult transformed the traditional view of that event into a technological and material one. Within this flying saucer Christology, Zeller identifies the Heaven’s Gate eschatology, or story of the end of the world, as a species of Dispensationalism. Fervent 19th century American Protestants read the Book of Daniel and decided that one day in heaven equalled one thousand years on earth, imagining each thousand-year period as a Dispensation. TELAH, the cult’s heaven, also experienced one calendar year for every thousand years on earth.

While a recognizable Protestantism formed the core of their soteriological and eschatological beliefs, the Heaven’s Gate cosmology, or understanding of the universe, drew upon a range of influences outside of the Christian tradition, but transmitted through the tradition of Christian Theosophy. “Like most religious systems, their beliefs were internally consistent and logical from the inside, though they seem circular and bizarre from the outside,” Zeller writes.

Although her payments lapsed, “Nettles was a member of the Houston Lodge of the Theosophical Society in America from February 3, 1966 to June 1, 1973,” and Applewhite studied Helena P. Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine after he met Nettles, Wessinger says. Both dabbled in astrology; Nettles even wrote a regular newspaper horoscope column. “Nettles inhabited a New Age subculture of disincarnated spirits, ascended masters, telepathic powers, and hidden and revealed gnosis,” Zeller writes. “She channeled spirits, including a nineteenth-century Franciscan monk named Brother Francis, held a séance group in her living room” that “channeled not only deceased human beings such as … Marilyn Monroe, but also extraterrestrials from planet Venus.”

Theosophy clearly had a great impact on the formation of Heaven’s Gate, just as it seems to show up in every UFO cult. In Prophets and Protons, Zeller observes that their “ufological vision also bears similarity to theosophy’s visions of the higher planes, especially as the I AM variant of theosophy proclaimed.”3 As we shall explore in a future essay, the founders of I AM were keen on the mahatma masters of Blavatsky as well as the aliens from Venus that she claimed to contact with her mind. As we have already seen in this series, this doctrine of “Ascended Masters” was very important to the earliest UFO cults, as it became important to Heaven’s Gate. Zeller adds in Heaven’s Gate that “I AM’s Ascended Masters generally existed in spiritual or extraterrestrial realms, and offered religious teachings through channeling and other spiritual means of communication.”

Importantly, the Ascended Masters were embodied, having “ascended” from Earth to the higher realms that they now inhabited. This approach— and especially the idea of embodied masters — became an important part of Heaven’s Gate’s thought.

Wessinger sees a “literalistic interpretation of such Theosophical doctrines as that there are graduated levels of existence/consciousness in the universe and that these consist of very fine, divinized matter at the highest levels and gross, dense matter on the earthly level.” Theosophy teaches a doctrine of “subtle bodies that operate on the subtle levels of existence, but … are unified with the gross physical body, and someone possessing enlightened wisdom can function consciously in all the bodies simultaneously.” We are multidimensional. Planets are “gardens” where these “eternal, genderless” subtle bodies grow.

Nettles and Appelwhite met in 1972, when she was already getting divorced. In 1973 they tried opening a New Age bookstore, where they sold theosophical material and practiced astrology together. When it failed after a few months, they relocated to the countryside at “Know Place,” a retreat center where they deepened their studies and taught their first spiritual students. Like every UFO cult studied so far in this series, Heaven’s Gate emerged from the dynamic beliefs of Christian Theosophy that informed the so-called New Age. That whole “Age of Aquarius” thing they sing about in the musical Hair? It’s Theosophical Dispensationalism. You are being proselytized.

Unidentified Flying Archons: How A Global Religion Reinvented Itself For A 'New Age'

The term ‘New Age’ has always been a false conceit in reference to the 1970s, or any time in the 20th century. American Christianity beheld a world of spiritual ideas during the 19th century. Across the globe, including the United States, new religions were forming around universalizing ideas of humanity. Hegel and Marx presented new revelations to explain

According to Robert Balch, who posed as a believer in order to study the group, during 1976 Nettles and Applewhite had a problem. Students were not committing as much as they wanted, or leaving the group, because they thought for themselves too much. They “solved the problem” of members claiming interpretive authority “by eliminating any possibility of individual revelation,” Balch says. Truth was only accessible to the student though the Older Member, a term they capitalized. “They explained that all information from the next level was channeled through a ‘chain of mind’ that linked the next kingdom to individual members through Bo and Peep,” as they were styling themselves at the time. This “chain of mind” was classic Ascended Masters Theosophy. Thus they “became necessary intermediaries between members and the next level.” Balch reports that students deepened their committment and there were fewer defections afterwards.

Three years after Nettles died, a Heaven’s Gate pamphlet claimed that Applewhite was in telepathic contact with her, thus speaking for her as well. She was his own Ascended Master. According to one ex-member, when Applewhite first raised the subject of suicide in 1994, he also mentioned that a message from Nettles had suggested the possibility.

Reincarnation, a Hindu idea transmitted through Theosophy, became an important part of the cult belief system too, especially after Nettles died. The human soul went through multiple incarnations until it learned how to “evolve.” While it “served an unclear role at the end of the movement’s existence,” Zeller says, “several ex-members confirmed that they believed it was a part of the group’s beliefs even at the end.” A “Next Level gland” located in the forehead also seems inspired by the “third eye” and Hindu chakras.

Zeller also points to Abraham Maslow and the so-called Human Potential movement, or American New Thought, or “positive thinking,” or the new popular term for magical thinking, “manifesting.” Prayers used by Heaven’s Gate reflect this “third major strand in American religious life,” as American religious historian Catherine Albanese has called it. “Heaven’s Gate is therefore part of a broader American religious tradition wherein adherents conceive of mental imagination as efficacious means toward bodily control,” he writes. The body, after all, was a “flawed container” that had to be overcome.

Nettles and Applewhite taught a form of ascetiscism. Before she died, the groups practices was aimed at a physical transformation of the biological body into a “perfected Next Level being.” After her death, Applewhite abandoned this literal interpretation for a mystical one, but continued the group’s ascetic tradition. From the beginning, group members were required to give up families, jobs, alcohol, drugs, and dating. Altogether, they had seventeen “steps,” or things to avoid, a number favored by numerologists.

Each true seeker of the next kingdom must literally walk out the door of his life, leaving behind his career, security, loved ones, and every single attachment in order to go through the remaining experiences needed to totally wean him from his needs at the human level. Until this frightening experience is underway, a man cannot begin to comprehend the reality of these “higher” and simple experiences necessary for this total metamorphosis into a new being.

Property and money were held in common. Everyone leaving the “craft” was required to carry $5 for bus fare and three quarters to call from a jailhouse payphone if needed, but this money was not their own. Eating regulations were altered frequently in order to encourage detachment from food, which they called “fuel.”

“The students regarded the monastic disciplines of the class as purifying their minds of the influences of discarnate entities and evil space aliens, which strove to cause humans to be attached to their human bodies (“their vehicles”), families, and traditional social roles,” Wessinger writes. Believers were free to give up at any time. “When people decided to leave after going through the socialization procesess of the class’s monastic discipline, it was usually not because they did not believe in the teachings, but because they doubted their ability to adhere to the monastic discipline. Usually when people left the class, they remained believers, and some returned later.”

At the beginning, converts “typically were young people in their 20s who were already involved in the counterculture, with few attachments,” Wessinger says. “The picture that emerges of converts to Heaven’s Gate is that of spiritual seekers who had become frustrated by their many pursuits, rejected the various alternatives within the existing religious marketplace, and in turn had begun to reject the very nature of human earthly society,” Zeller writes. James Phelan, a journalist with the New York Times, was able to interview members and ex-members during the 1980s. They were from all over America and they had followed every spiritual path.

One man joined Heaven’s Gate because of a longtime fascination with UFOs, another called herself a lifelong spiritual seeker, a third was raised Catholic, but trekked across the country to find the group and described it as the “first time in my life [that] I have a firm faith that there is something higher.” Others included an agnostic who experimented with hallucinogenic drugs and looked for meaning in the stars, and a Jewish seeker from New York who had journeyed to Israel and India to try kibbutzim (communes), drugs, and gurus. Phelan summarized his subjects as sharing “one common denominator among almost all the converts. Almost all are seekers . . . They have spent years, in the trite phase, ‘trying to find themselves.’ Many have tried Scientology, yoga, Zen, offbeat cults, hallucinogens, hypnosis, tarot cards and astrology. Almost all believe in psychic phenomena.”

Yet the eternal fate of the soul “did not qualify as a religious or spiritual concern” with Heaven’s Gate. Rather, Applewhite insisted that their revelation was “scientific — this is as true as true could be.” Like Theosophy, they held science to be sacred, a source of truth and rationalism and evidence, whereas religion “possessed falsehood, emotionalism, no sensibility, and reliance on faith,” Zeller explains. They were not scientists, of course, therefore “the group said little about science until its final years, but throughout its history it tried to ‘be scientific’ by offering naturalistic, materialistic explanations of religious concepts.”

For example, the duo couched their theology in terms like “biology” and “chemistry” rather than spirituality. All humans had souls, but in a strangely Calvinist turn, only some human “containers” had a “deposit” which could develop into a Next Level being. “The deposit, however, clearly functioned within Heaven’s Gate thought as a technological analog to the human soul,” Zeller writes.

Nettles and Applewhite went much further than Theosophy in rejecting all religions “as a category and form of knowledge,” Zeller says. The 1992 “Statements by Students” document contains several explicit attacks on religion in general by members of Heaven’s Gate. Towards the end of his life, Applewhite even declared that the Theosophical tradition was “Antichrist.” Wessinger writes that this was “probably due to its Monism,” the doctrine that only one supreme being exists. Zeller says that after Nettles died, Applewhite became increasingly dualistic and Manichaen, splitting the world into good and evil spheres of influence, rejecting all other religions as falsehoods intended to mislead mankind from the truth.

Whereas Heaven’s Gate embraced materialistic naturalism — the foundational idea of science — they relied on deduction and revelation to determine truth. They were, in the end, a religion. If scientific evidence conflicted with the ideology of the cult, they dismissed it. “Empiricism could not replace scripture and the teachings of the movement’s leader,” Zeller writes. They were hardly the first religious teachers of the modern age to try, and fail, incorporating science into their bricolage. Indeed, we can recognize scientism, that is, a faith in science to perform miracles, in Heaven’s Gate.

Science, Fiction, and the Magician: How L. Ron Hubbard Conjured Scientology

An audio version of this post is embedded below the paywall. All posts are now archived after 4 weeks. Lafayette Ronald Hubbard did not create Scientology from original material. For example, “in his early Dianetics practice we can see clearly the influence of Freud, Jung, and other thinkers available in the mid-twentieth century, as well as the influence of popular self-help works such as Norman Vincent Peale’s best-selling

Like all cults worthy of the name, Heaven’s Gate began with a spiritual revelation in 1973. “While camping in Oregon,” Nettles and Applewhite “realized they were the ‘Two Lampstands’ or ‘Two Witnesses’ mentioned in Chapter 11 of the Book of Revelation, who have come to spread the word of God’s impending judgment and salvation,” Wessinger writes. While she was alive, this progression of the soul was supposed to be physical, instant, and without the need for disembodiment by death.

When Brad Steiger, a UFO researcher, encountered the young cult in 1976, the pair told him that flying saucers are “actual means of transportation that serve as protection and an expedient function of travel. Members of the next level do not flap around on wings, and they are not spirits that can just travel with a swift process of the mind.” Astral travel and spirit-travel were ruled out. Nor were aliens angels, even if they filled the role of angels. “Next-level aliens, Bo and Peep insisted, possessed physical bodies and were therefore real, unlike more spiritual conceptualizations that other religions might possess,” Zeller writes.

The Two equated reality and materialism, and implied that the spiritual, which empiricism could not verify, represented falsehood. For the Two, science offered a rhetorical opportunity to distance themselves from the suspect category of religion.

From 1976 until Nettles’s death in 1985, “The Process” of reaching the Next Level remained materialistic and natural, a metamorphosis. After her death, Applewhite reimagined The Process as “shedding of the vehicle.” During those twelve years without his spiritual partner, Applewhite “transformed the group’s understanding of salvation, eschewing the materialistic naturalism of [their] early days and adopting a more spiritual concept of the transmigration of the soul.” The bricolage was never quite finished.

By 1991, the cult believed that their mind and consciousness would transfer into their new bodies at death like magic: spiritual travel was back in. The now-problematic old doctrine, Human Individual Metamorphosis (HIM), was replaced by Total Overcomers Anonymous (TOA). “Individuals will be lifted up onto the spacecraft if they have overcome,” Applewhite told them. What they had to “overcome” was their biology.

Nettles and Applewhite taught their students that aliens have no sex organs at all. The very last poster produced by Heaven’s Gate declared that the Next Level itself “is a genderless (sexless), non-mammalian (though certainly nonreptilian), crew-minded, service-oriented world that finds greed, lust, and self-serving pursuits abhorrent.” Wessinger notes that Heaven’s Gate adherents habitually wore “hooded windbreakers and loose clothing to conceal sexual characteristics.” It was a conscious imitation of the genderless, small-mouthed, pleasant, peaceful aliens of TELAH. “When they were found as a group suicide in the spring of that year, the first law enforcement officers on the scene assumed that they were all men because” of their uniforms, Robert Howard Glenn writes in “Rhetoric of the Rejected Body at ‘Heaven’s Gate’.”4 “This community sought to minimize gender roles and the sexuality that those roles imply. In the end, this rejection became so radicalized that it led them all to the choice to negate their human identities completely through suicide.”

Applewhite and Nettles were both divorced. He had two children, she had four, all abandoned when they dropped out of society together. It was, by all accounts, a purely spiritual partnership. Reports that Applewhite had an affair with a male student at one college campus, or a female student at another, leaving both in disgrace, are unsubstantiated by scholarship. Internalized homophobia does not suffice to explain Applewhite’s trajectory, either. Rather, their objections to sex were monastic objections, for they were ascetics imitating the “seedless” TELAH beings. “From Applewhite’s own testimony, it is not so much that any particular sex acts are morally wrong, it is instead that anything that reminds him of his physical human body … is a misdirection of energy.”

A student who went by the cult name Jwnody described “the physical characteristics of our species” on the Next Level as “genderless and very pleasant looking, oftentimes somewhat childlike or wisely gentle in their appearance.” Next Level beings, Jwnody said, were “non-mammalian,” “non-seed-bearing,” “eternal,” and “everlasting.” In addition to uniforms, the students became “immortal, genderless, perfected beings, in many ways alien to our human condition” by adopting cult names, all ending in “-ody” meaning “child of God,” a practice that was systematic after 1977, Zeller says. In his fourth published prayer, Brnody asks for assistance “maintaining non-mammalian behavior of the Evolutionary Level Above Human— around the clock— in order that my soul (mind) will be compatible with and able to occupy a genderless vehicle from the Next Kingdom Level.”

Heaven’s Gate was steeped in the Outsider culture of America at its beginning. An itinerant lifestyle and countercultural values added to the demands that the cult made on its members. Applewhite was “radically attacking” American civil religion “through the performance of his identity not only as a New Age ascetic, but, even more, as the bodiless trans-dimensional being that possessed it,” Glenn writes. Invoking Judith Butler and the impenetrable language of postmodernism, Glenn makes Applewhite’s performance of an identity into a rebellion against The Man and The System rather than an expression of faith. “Applewhite performed a completely asexual identity. And he performed that identity as a radical break from even the most social taboos of the Protestant Americans Christianity of his upbringing,” Glenn argues.

Glenn suggests that Applewhite’s rebellion against that upbringing led the group to the mass suicide. He discounts the meaningfulness of their bricolage. The “simple shifting of Christian beliefs into a UFO-based belief matrix in a damning reaction against popular Christianity brings to light the conflicts inherent in his own desire to escape the Christian system while knowing, aparently, little else.”

Zeller contends that Heaven’s Gate was primarily a Protestant Christian cult, and animated by genuine faith. Ti and Do had an annotated bible. “Specifically, most of their notations fall within the Gospel of Luke, which scholars identify as the gospel most emphasizing Jesus as both biographic exemplar and savior of the world.” Nor were they puritanically anti-sex, or opposed to sexuality. In fact, Ti and Do purposefully and systematically introduced sexual tensions to the cult, leading “to anxiety, self-consciousness, and sometimes conflict.” Following a pop-psychology formula of aversion therapy, the two “hoped that these feelings would prove cathartic in helping their followers overcome their human attachments, emotions, and especially sexual attractions.”

In practice, members of the movement lived alongside their partners, sharing material possessions, money, and physical space with their partners, and traveling alongside them as a dyad. Since the group’s leaders assigned partnerships with an eye toward increasing friction, during the first years of the group’s existence they made sure to assign heterosexual men and women as partners, and keep gay men or lesbian women together in same-sex pairings.

This was exactly the “overcoming” initiates had to do, and it explains why the male-to-female ratio of the 38 dead cult members in Rancho Santa Fe was almost exactly even. According to survivors of the cult, this was “the most difficult practice of the group,” Zeller says.

Nettles’s death started Applewhite’s “shift toward an eschatology predicated on mind-body dualism, a neo-Calvinistic notion of election and predestination, and increasing apocalyptic expectations. All of these permitted and even encouraged the development of a theology supportive of suicide,” Zeller says. Where he blames the Heaven’s Gate mass suicide on maladaptive Protestant Christianity, Glenn identifies the rejection of Christianity and the sexed body of Protestant capitalism as the cause.

Neither of these explanations satisfies to explain Applewhite. Age, poor health, and loneliness for his spiritual consort seem more immediate causes of depression leading to suicide. In 1995, the group abandoned their project to build a “Launch Pad” in rural Manzano, New Mexico. “It was just too hard to keep doing,” members said. Applewhite was 63 years old, too old for pioneering. As the group relocated to Phoenix, Arizona, Applewhite and at least seven other male members of the cult elected to “have their vehicles neutered … in order to sustain a more genderless and objective consciousness,” in their own words. In his exit video, Srrody rejected “hormones that keep the body intoxicated, stupid, empty-headed, and ‘blind.’”

Applewhite did not lead the way into castration. “The chronology is unclear, but either Srrody or the partnership of Alxody and Vrnody engaged in the procedure first, in 1994 or 1995, followed by Applewhite himself,” Zeller writes. “Four other members underwent the procedure according to autopsies performed after the suicides two years later.” Rather than spiritual transfiguration, Applewhite experienced “long-lasting and unpleasant complications” from the procedure. He was already dealing with a heart condition. The group had ceased holding public meetings because no one ever showed up to them anymore. “Neoody recounts that these failures, especially in August [1994] in New England, resulted in Applewhite’s decision to halt active proselytizing and once again retreat to cloistered living,” Zeller notes.

When they had preached together, Applewhite and Nettles declared their own imminent martyrdom. Per Chapter 11 in the Book of Revelation, they would lie dead in the street for three days before a resurrection by alien technology. They called this the “Demonstration,” and when it did not happen, they rationalized the failure of the prophecy as a metaphorical media martyrdom: the newspapers had made them sound like cranks, assassinating their characters. Known as “the delay of the parousia,” this is a common problem for prophets, but easily solved by the faithful community. When events do not go as foretold, people find a new way to keep believing.

Throughout his ministry, Applewhite continued to maintain the government would come for him. At one point, the group purchased a small supply of firearms, but of course they knew even less about shooting than they knew about doom-bunker engineering, and gave it up. “Paradoxically the absence of any overt oppression led adherents to decide they had to end their own lives rather than rely on the government to kill them,” Zeller says. He argues “that the lack of government persecution against the movement was far more influential than any other factor in pushing the group members toward deciding to commit suicide, as their past statements indicated that they expected this to happen imminently.”

In his final messages, Applewhite clearly craved apocalypse. He called upon the radical fringe to rise up, telling the religious cults and right-wing militias of America that “they will be set aside—‘put on ice,’ so to speak— and have a future, have another planting in the next civilization for further nourishment.” They too could be martyrs. Exit statements by the group reflect an inability and unwillingness to live without their Older Member. Without him, they had nothing to live for. “Because there was no prospect of creating a new generation of [group] members there was no need to form a truly lasting community” either, Glenn adds.

Heaven’s Gate believed in their own opposition as spiritual agents. Though alien in origin, the Luciferians were not genderless or team players or pleasant. They were “programming” society with false gods and a gnostic false consciousness to prevent humans from reaching TELAH, or even knowing about it. Shortly before the suicides, Anlody wrote that “earth and its human level are the hell and purgatory of legend. It wasn’t meant as a place in which to get comfortable or to stay.” Rather, our world is supposed “to separate the renegades of Heaven — the Luciferians — from those who have risen above the human level, and a place to test souls striving to get” there.

Zeller writes of this oppositional narrative that Heaven’s Gate “upheld two forms of dualism: one a metaphysical dualism that distinguished the body from the true self, found in the mind or soul; the other a second form of dualism that I call ‘worldly dualism,’ which distinguished the members of Heaven’s Gate and their movement as good, saved, and wholesome, and separated from a bad, damned, and corrupt outside world.” Psychologists call this phenomenon “splitting.” Robert Jay Lifton, who studies both communist and fascist regimes as cult movements, calls it “doubling.” Whatever we call it, the result is often violent.

Problematically, however, Heaven’s Gate could not attract a violent opposition. The government was not coming for them. Luciferians did not show up to fulfill the prophecy by taking their mortal lives. Luckily for the group, there was a brand-new way to find opposition in the world: the internet.

As one student with the cult name Rkkody told a researcher, the group’s final recruitment campaign, which took place online, “was directed at locating and bringing home” people who had deposits. They started with a UseNet post in 1995 that explicitly predicted a government raid on themselves. “Because of the overripe corruption of the present civilization, this is the last scheduled visit before its recycling. It is the End of the Age. The human population, under space alien ‘thought domination,’ has become irreversibly perverse and rotten.” Their message called for everybody to get armed, get ready, and then await annihilation by the government so they could all go to heaven in a spaceship, too.

Unsurprisingly, “members reported ridicule and heckling rather than support, and the lack of public interest in their message highlighted their earlier suspicions from 1994 that the time for earthly engagement must be coming to a close,” Zeller writes. At last, they had found people willing to destroy them, even if only in a comments section. “Ironically, these outreach attempts probably served as the final impetus for the decisions to turn inward and end the group’s existence.”

“It was clear to us that [our beliefs] being introduced to the public at that time was premature,” reads the final Heaven’s Gate anthology. Several more posts in 1996 had “similar results.” A former member told Robert Balch and that “we just were not able to interface with the public” and “it was time to leave.” They were just waiting on a sign from the heavens, now.

“All we glorify really is the possibility that we as humans are more than we appear to be. I have an opportunity to push in that direction, and I do. I have an open mind. I'll listen to anybody.” - Art Bell, TIME Magazine interview

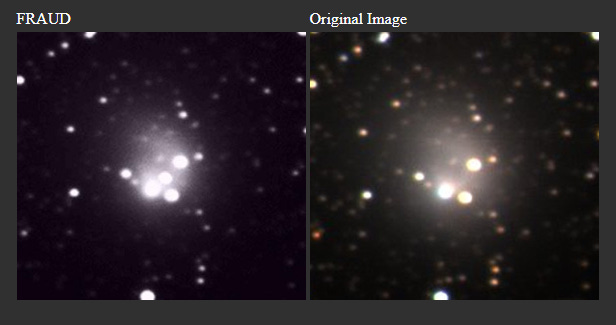

According to Balch and Taylor, the Kohoutek comet of 1973 inspired the astrologers Applewhite and Nettles to work together in the first place. “Looking to the skies for meaning therefore was hardly new for Heaven’s Gate,” Zeller writes. Now a second comet heralded their reunion and the end of their mission on earth. Hale-Bopp was real enough, but during the 14 November 1996 broadcast of Coast to Coast, a nationwide AM radio program, the comet gained a mysterious “companion” that was entirely fake.

Defending himself in a TIME Magazine interview two weeks after the suicides, show host Art Bell blamed his guest for the controversy. "I started getting a lot of messages saying, 'Art Bell, you killed 39 people.' It's important to understand that the only person who ever said there was a spacecraft following Hale-Bopp was Courtney Brown,” and Bell himself ultimately denounced the photograph prior to the suicides.

Of course, Bell had been quite excited by the photo on the night of the broadcast. He spoke to Chuck Shramek, the amateur astronomer who had supposedly taken the image of the so-called “companion.” The day after the broadcast a University of Hawaii astronomer named David J. Tholen exposed the image as a digital hoax someone had made using his own photograph. The not-at-all-mysterious object in the image was a mere star, SAO 141894, rather than a ringed planet four times the size of earth, as Courtney Brown claimed.

Brown was already a subject of public controversy about academic freedom. A tenured professor of political science at Emory University by day, Brown ran a “remote viewing” educational concern called the Farsight Institute, which reputedly charged $3,000 to teach students how to be psychics, by night. An Emory psychology professor named Scott Lilienfield defended his colleague’s academic freedom to do as he likes in his spare time, but also challenged Brown to demonstrate his alleged remote viewing program in a laboratory setting, an offer that Brown has never accepted.

Brown and his institute are still active. He claims a pedigree from the famous Stargate Project, a US Army program to investigate elements of the New Age, the paranormal, and the human potential movement for applications in American defense during the 1970s and 80s. Author Ron Johnson’s 2004 book The Men Who Stare At Goats, which was adapted into the 2009 film of the same title, is about people involved in the Stargate Project, though Johnson does not mention the program by name. “Remote viewing” is in fact a very old spiritual and theosophical script. Brown was speaking in the cult language of the flying saucer bricolage that had developed over centuries, that took flight in UFOs after World War II when Christian Theosophists began “encountering” men from Venus. Brown had already authored a book, Cosmic Explorers, about remote viewing and aliens. For Brown, then, the five-hour program was an opportunity to promote his ideas about extraterrestrials and spirituality to a highly-engaged national audience.

For the Heaven’s Gate cult, especially Marshall Applewhite, the program was a kind of revival meeting.

The entire program is currently archived at this YouTube link. It has a charming 1990s feel, with listener messages arriving by fax machine, websites being broken by traffic demand at dial-up speed, and speculations about President Bill Clinton’s state of mind. Brown speaks of a “soul and the subspace mind” and a “composite nature of life,” earthly and heavenly. The alleged object, which “seems to be moving under artificial control” behind the comet, was “emitting light” that can be understood through a “decoding process,” somewhat like the final reel of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. According to Brown, “most of what it’s trying to say has to deal not just with the physical realm but the subspace realm of life.” Whereas “the whole galaxy out there is aware of this composite nature of life,” earthlings were still ignorant, being held back by “decades” of government secrecy about flying saucers. The “reigning power is preventing proper decoding” of the “vibrational instruction” from the mysterious ringed planet, Brown said. Why? They were too afraid of the aliens. He knew because they had remote-viewed the vice president, Al Gore, to be sure.

“Something this big is going to produce fear,” Bell interjected. He returned from breaks with a warning for listeners: “If there are children in the room, please get them out.” He wanted to know how long Bill Clinton had known, and how long the government had known, about the approaching comet companion.

The “guidance system” of the spaceship, Brown claimed, was “sentient … somehow aware of itself as to point of origin,” a “composite of minerals and organic material in a matrix of thought,” its existence both “subspace and physical.” It was subtle bodies doctrine.

The people on board the spaceship were diverse, because “all beings are involved … humans were involved in the days of Atlantis.” Quaintly, Brown claimed that of the planetary passengers, “some are Martians here to save us from a natural disaster.” Humanity had known for two decades that no life existed on Mars. It was ancient astronaut theory, a New Age trope inherited from Christian Theosophy. Applewhite and Nettles “took Zacharias’s statement that the Lord ‘hath visited’ Israel literally, as evidence that the extraterrestrial being worshipped by the Israelites literally visited his people, making the Bible in fact a record of alien visitation,” Zeller explains. Crashed saucers, alien corpses, and government cover-ups of those things, as well as alien ‘abduction’ narratives, appeared in the Heaven’s Gate ‘88 Update. By 1996, these tropes had suffused throughout the culture thanks to The X-Files. They had been subsumed into the brocolage.

Brown described the order of the galaxy as another variation on Ascended Masters doctrine as transmitted through Christian Theosophy. “Wherever there are beings, they organize themselves,” he said. A grand human “event” was being organized. A “galactic council” and a higher order of beings were “very serious about this event,” in which a swarm of “hundreds of thousands” of spaceships would leave the mothership and visit every corner of the earth to spread the gospel of their own existence. This Rapture-like prophecy was meant as pure display, for “they know theater.”

By “they,” Brown meant “the grays,” the genderless extraterrestrials piloting the spaceships. Referring to the human-alien hybrid trope, Brown said that the grays know “their future selves are half-human.” They are, after all, “composite beings.” We ought not to fear them, Brown argued, because they are “benign, good, and gentle” in nature. “We’re not supposed to be afraid of them,” he reassured Bell.

Still, Brown admitted to an element of danger. The psychics of the Farsight Institute described a mixture of “technological, artificial, and natural” elements to the Hale-Bopp companion that included “borrowed technology” the spaceship passengers did not understand themselves. Of the beings on board, “some of the people are ignorant and dangerous” — they were what Heaven’s Gate called Luciferians. A tendency to problematize the aliens, with some being incompetent and still others evil, can be discerned throughout the postwar Christian Theosophical UFO cult bricolage.

Breathless with explanation, because his report from the psychics is dozens of pages long, Brown breezes past all the familiar tropes, for “time is of the essence and many things are happening.” Five hours is so little time when such a momentous occasion is imminent. He told Art Bell that a “top ten university astronomer” had confirmed the material in his dossier of extrasensory perceptions. He promised that the astronomer would reveal himself to the world in ten days and confirm everything. When that time expired, and the astronomer had not come forward, Bell called foul on the entire hoax.

But Brown’s extended performance of scripts had resonated with the Heaven’s Gate theology and their bricolage of beliefs. Such strong evidence was enough on its own, for them. Applewhite dismissed the meaningfulness of a physical “companion” in his final written statement. The believers simply ‘knew’ that it was time, whether or not the ring planet-spaceship was real. On 26 January, they bought patches reading “Earth Exit Monasteries” for their outbound journey, but changed their minds and decided to have the “Away Team” patches made in February. They were fussing over the details of their exit to the Next Level. The song they had waited so long to hear had finally been sung.

Riffing on a recipe from Derek Humphry’s Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying, published in 1992, they elected to put powdered barbiturates in applesauce, rather than yogurt or pudding per the book, drink vodka, and then put plastic bags over their heads. Other members would remove the bags and place the shrouds over the faces of the dead. They recorded their final messages to the world. Working in teams, fifteen “students” died on the first day of the ritual, then fifteen more died on the second day, with Applewhite and his last six companions leaving earth on the third day. The last two members of the cult to die, both women, were found with bags still around their heads.

First, the group posted their final website update, appealing to the believers to come join them, whenever they are ready. Additionally, “they indicated websites and other Internet sources associated with the New Age and channeling, alternative healing and science, ancient prophecies, Gnosticism, libertarianism, government conspiracies, and a plethora of UFO-conspiracy oriented websites,” Zeller observes. They selected a living believer, someone who did not live in the home but kept their faith, to find their bodies and report the completed ritual to the world.

Comparing Heaven’s Gate to other violent millennial cults, Wessinger writes that “it is remarkable that Heaven’s Gate’s violence involved only consenting adults who wanted to exit earth.” They did not attempt to kill or persecute their enemies. Zeller proposes that “there was a very clear reason that members chose suicide: because they did not perceive the actions they chose as suicides. They looked to them merely as a form of graduation from an unwanted terrestrial existence on an undesirable planet in disagreeable bodies, to a cosmic existence in the Next Level in perfected new bodies.” They were already more alien than human, unable to identify with fellow earthlings.

While they excoriated all existing religions as “corrupted by malevolent space aliens,” the Heaven’s Gate cult never really stopped believing in their bricolage. There was nothing new about these ‘New Age’ beliefs. Indeed, the bricolage hed been developing for centuries.

In 1758, Emanuel Swedenborg published The Earthlike Bodies Called Planets in Our Solar System and in Deep Space, Their Inhabitants, and the Spirits and Angels There, Drawn from Things Heard and Seen. As we shall explore in a future essay, Swedenborg was a scientific man who had a religious experience in his fifties and began communicating with aliens on other planets, starting with the moon and Mars. Consider this passage from Swedenborg about the residents of Saturn. Emphasis added:

When others try to lead the spirits from that planet astray and tear them away from their faith in the Lord, from their humble attitude toward him, and from their upright way of living, they say they want to die. Small knives then appear in their hands, with which they seem to be trying to stab themselves in the chest. When they are asked why they are doing this, they say they would rather die than be taken away from the Lord. Sometimes spirits from our planet make fun of them because of this and harass these upright spirits for behaving this way. The spirits reply, though, that they know perfectly well they are not actually killing themselves. This is just a projection that flows from what their lower mind desires: that they would rather die than be drawn away from their worship of the Lord.

Inspired by Swedenborg’s various writings, and invoking his name like a famous magician, Honoré de Balzac published a novel, Séraphîta, in 1834. Balzac’s plot is a love triangle. The titular character, Séraphitüs-Séraphîta, is a perfect androgyne, neither male nor female, a being who has transcended humanity and human sexuality through Swedenborg’s doctrine, and is beloved by both a man and a woman at the same time. Genderlessness turns out to be a common theme in modern gnostic philosophy.

The website still exists. Like most works in the Christian Theosophical UFO bricolage, it has not aged well, a throwback to HTML coding in Notepad. “It will never be updated and its purpose is to act as a historic marker for civilisation,” say Mark and Sarah King, survivors of the cult and owners of the TELAH Foundation. They also say that Heaven’s Gate is closed, but who knows? In a material world where “genderless beings” seem to be more numerous all the time, and the ideas of Unabomber Theodore Kazcynski became disturbingly popular before his death, maybe Heaven’s Gate were simply ahead of their time.

Two more students of Heaven’s Gate, Wayne Cook and Chuck Humphrey, attempted the same ritual together after Cook talked to the CBS show 60 Minutes. Cook died, but Humphrey was revived by paramedics. He finally succeeded in achieving his transmigration during 1998, out in the Arizona desert, by inhaling carbon monoxide. Humphrey was near Sedona, one of the “high energy places” to which Marshall Applewhite and Bonnie Nettles directed followers on their spiritual pilgrimages. A New Age Mecca, it is where Sister Thedra, leader of the Association of Sananda and Sanat Kumara, ended up living out her days as a Christian Theosophist and UFO cult leader. The further we explore the phenomenon of flying saucer faith in this series, the more connections we find.

When Theosophy Fails: Flying Saucers and the Defining of Cognitive Dissonance

Published in 1956, When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group That Predicted the Destruction of the World is one of the most famous psychology texts of all time. Two years earlier, lead author Leon Festinger and a team of academic observers from Chicago had watched a small cult in Oak Park endure the “disconfirmation” of their prophecy that the world would end on 21 December, 1954. This message had come to earth from “Sananda,” the risen Jesus in heaven, yet the world had failed to end on schedule, and the expected flying saucer had not arrived to evacuate the believers as promised.

Zeller, Benjamin. Heaven's Gate: America's UFO Religion. NYU Press, 2014.

Wessinger, Catherine. How the Millenium Comes Violently: Jonestown to Heaven’s Gate. Seven Bridges Press, 2000.

Zeller, Benjamin. Prophets and Protons: New Religious Movements and Science in Late Twentieth-Century America. NYU Press, 2010.

Howard, Robert Glenn. “Rhetoric of the Rejected Body at ‘Heaven’s Gate’.” Brasher, Brenda E., and Quinby, Lee, editors. Gender and Apocalyptic Desire: Millenialism and Society. Routledge, 2014.