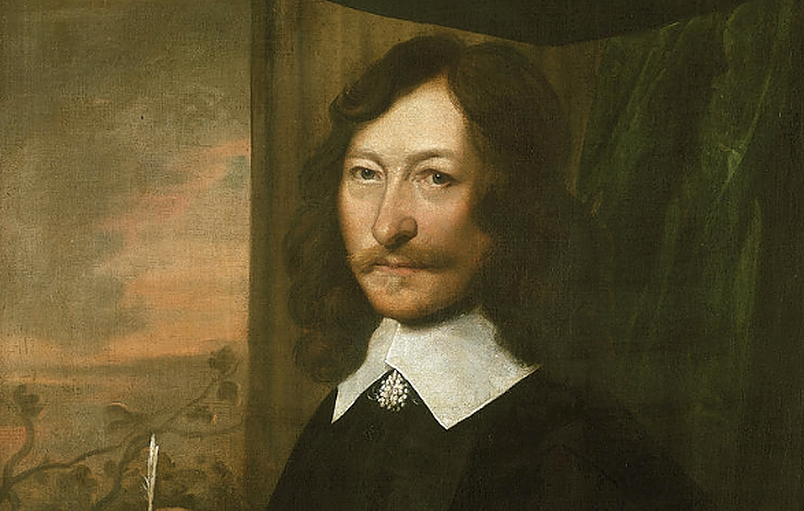

Like the best frauds, the inventor of modern astrology often started his pitches by calling out his critics and rivals in the art of confidence to make himself seem the more reliable informant. In the opening of his pamphlet on monarchy in 1660, for example, William Lilly warns readers of a “Spirit-Mongring Mountebank-Quack” who “cheated Mr Birt of £100…

Substack is the home for great culture