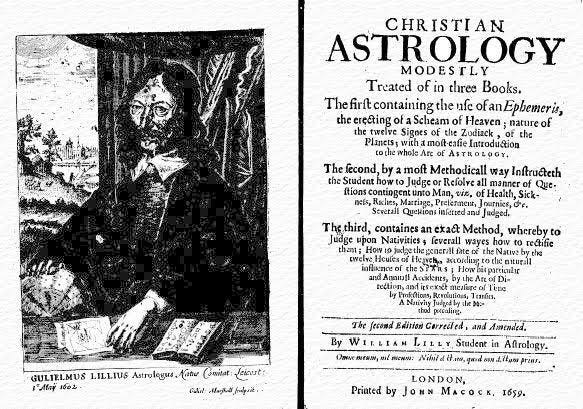

William Lilly was “unremarkable” in appearance, according to author Jessie Childs. “He had dark shoulder-length hair, a moustache and slightly river-blasted cheeks.” Lilly was in his 40s at the height of the English Civil War, when he began publishing almanacs of horoscopes. These “sold well to an anxious public,” Childs writes. England’s troubles were …

Substack is the home for great culture