What 'The Left' Still Gets Wrong About Iran

1979 was a 'bourgeois revolution'

In his 1993 book Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic, Ervand Abrahamian writes that what happened in 1979 was a “bourgeois revolution” all along. Shi’a clergy used leftist rhetoric to frame themselves as saviors of the people from the despotism of the Shah throughout the 1980s, leaving no room for a political left. Indeed, if there was a ‘reign of terror’ during the Islamic Revolution, Abrahamian says, then it was against the Iranian left.

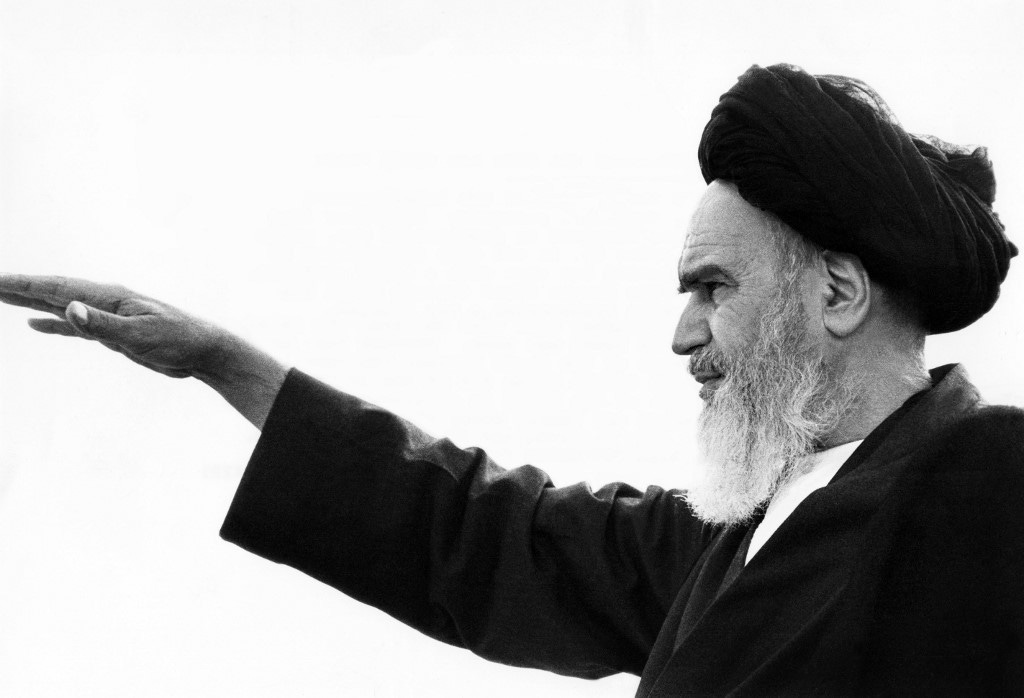

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was quite acceptable to the middle class. While the rhetoric of his smuggled exile audiotapes was populist, once returned to Iran and put in power, he mainly confined his appeals to Iran’s middle class. Indeed, it was the bazaar, that ancient commercial guild in Tehran, which gave the crucial spark to his revolution. After the Shah replaced their chamber of commerce with a puppet organization, the retail merchants of Iran retaliated by creating the Islamic Coalition Society (Mo’talafeh). It was the beginning of the end for him.

As Supreme Jurist, Khomeini constructed an entire parallel state of clerical institutions in order to have a civil service free from the political clash of left versus nationalist factions. Provision of social services, especially relief, through these bonyads gave the clerics a new set of foot soldiers to replace the leftists who had taken part in the Revolution.

As the left became unnecessary, it also became a target.

With the Soviet Union still around, the communist Tudeh Party could not help but be seen as yet another foreign influence in the country. Furthermore, the clerics were from mixed class backgrounds, argued Ali Khavari, General Secretary of the Tudeh Party. Writing for the World Marxist Review in March 1984, Khavari’s dark mood was expressed in the title of his essay, “Torturing the Party to Tear Up the Revolution.” Gloom was justified by that point. His predecessor, Nasreddin Kianouri, had been arrested, tortured, and forced to recant in a public broadcast on May Day in 1983.

Writing for the World Marxists Review in April 1979 without naming Khomeini or the Islamists of Iran, Kianouri had predicted their revolution would “try to move closer to the reactionary elements which have been left from the old regime and to prevent any deepening of the popular and democratic content of the revolution.” Kianouri died under house arrest in 1999. Following his recantation of Marx, other Tudeh Party leaders made similar statements, and the party was outlawed.

Khomeini’s Byzantine constitution was an absolute hindrance to all reforms, let alone leftist ones. Between 1981 and 1987, the Guardian Council vetoed more than a hundred land, housing, labor, and tax reforms submitted by the Majlis, holding them incompatible with the protection of private property in the Qur’an. Utopian redistribution projects were out of the question in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Meanwhile, leftist leaders were systematically arrested and ‘re-educated’ into regime converts (tavvab saazi). Most of this campaign focused on the campus. Khomeini declared the necessity for a “cultural revolution” against “subversive leftists” and “atheists” in the universities during a speech in 1980. Reaction from his street army was swift.

“In the evening of that day, right-wing paramilitary forces called Phalangists, after the Lebanese Phalangist forces that were fighting the leftist forces in the civil war in that country, laid siege to the Teachers Training College of Tehran,” Muhammad Satami recalled in a 2009 essay for PBS. “The campus looked like a ‘war zone,’ according to a British reporter, and one student was reportedly lynched.”

Other campuses around the country did not fare any better. Over the next two days, offices of leftist students at universities in Ahwaz, Isfahan, Mashhad and Shiraz were ransacked, leaving hundreds injured and at least 20 people dead. The violence then spread to several campuses in Tehran, particularly the University of Tehran, which has always been a hotbed of political dissent.

All the universities were shut down on June 12, 1980, and did not re-open until two years later. Officially, the goal was the "Islamization" of the universities, which was an absurd notion. (How, for example, do you "Islamicize" the natural and medical sciences, or engineering?) It was really just a guise for exercising oppression and repression.

Satami recalled his own brother’s disappearance and execution during this period, the harassment of family who visited the grave, and three different headstones that militants broke trying to break his family. A state-driven media campaign encouraged the public to turn in violent Maoist fedayeen and Marxist mojahideen, while clerics reframed the left as enemies of Iran who had “always undermined the people’s revolution.”

Perhaps the reader is now wondering why ‘the left’ (broadly and globally defined) has more than its share of enthusiasts for the Iranian oligarchy, which does not resemble any sort of ‘leftist’ or ‘progressive’ program whatsoever.

One reason is obvious. Israel is the universal symbol of everything wrong with ‘settler colonialism,’ capitalism, and western imperialism, that is, everything that ‘the left’ hates. Thus support for Palestinian violence (‘decolonization’) is also a form of motivated reasoning. In this thinking, Iran is a useful counterbalance to the United States of America, source of all evil in the world.

However, the formative and less obvious answer is Michel Foucault, the father of academic postmodernism, and his thirteen ridiculous essays praising the Revolution during 1978.

While teaching in Tunisia during the 1960s, Foucault found a permissive environment for his pedophilia. He mistook this experience as representative of the wider Muslim world and projected his own wishful thinking on Iran, which he imagined as the vanguard state of a new world of sexual freedom, for some reason.

A huge fan of sadomasochism and sensual brutality of all kinds, Foucault had a blind spot. “A deeper cause to Foucault’s persistent misreading of the Khomeini revolution” was “his deep disdain for women,” David Frum writes. Reviewing the 2005 book Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism, he summarizes:

The Khomeinites never concealed their determination to shroud and subordinate women. This intention did not bother Foucault. In all his many writings denouncing the evils of post-Enlightenment society, the status of women was one theme that had never much interested him. Indeed, as Afary and Anderson point out, at the moment of his deepest engagement with the Iranian revolution, Foucault was at work upon the books he regarded as his masterwork, his History of Sexuality — a history that treats the emancipation of women in the later Graeco-Roman period as a catastrophe that put an end to the happy classical period when reproductive sex was regarded as an unpleasant duty, with pleasure to be sought between men and boys.

As we have confirmed in just the last few days, the elements of ‘the left’ that love Iran also do not care about the fate of women in the clutches of Hamas terrorists. These people are not blind or stupid when they celebrate what they see. Like Foucault, they see what they want to see in Iran — and pretend that what they see happening to women doesn’t matter.