We Are All Prisoners Of Democracy

Or, how The Village is constituted

“Free For All” is perhaps my very favorite television episode of any show, ever. Watching it for the first time in 1993 eventually led me to pursue a bachelor's degree in political science in 2001. Globalization was the hot topic of that time, a theme very consonant with this show, so I read into the literature of globalization as part of my education.

This particular episode is ostensibly about politics, but the political science of The Prisoner is not a matter of polling, opinion, or voting. Rather, The Village is an artificial world that can only exist in a culturally-quantum state of globalization, like a theme park. In fact Portmeirion, the Welsh tourist village that served as the shooting location for The Village, is a vacation resort and a product of globalization.

Patrick McGoohan’s enigmatic series thus presents us with a Disney Land democracy featuring a perfectly-manicured mass politics under a panopticon of control. The Village resembles the vision put forward by World Economic Forum guru Klaus Schwab, for in The Village, residents want for nothing, but also own nothing, especially themselves.

Number 6, the prisoner of the title, resents the omniscient surveillance and omnipresent power of The Village, the stifling oppression of difference, the stiflingly ecumenical society. Everything, including the radio set in the apartment assigned to Number 6, is a control device. Even the climate of Portmerion seems to be under someone’s control.

Technology makes The Village a utopia for liberal managerialism. Its constitution is a political technology. The System is not explained in The Prisoner, nor is it mentioned as The System, but it is evident throughout the series. The System stifles both radical and reactionary. Globalization too has its malcontents on the political left and right, for it has no real native constitutency outside of administrative, educational, and cultural elites. Perhaps the reader will see why this particular episode grew so well on me, indeed I like it more all the time.

The entire plot of The Prisoner can be summed up in the three-minute opening montage that introduces every episode. Our protagonist, a British secret agent, resigns his job in protest against … something. It isn’t very clear what set him off. Then we see the nameless former agent being cancelled with machine efficiency using what was state-of-the-art information storage technology in 1968, the year this series first aired in the United States. We then watch Number 6 being knocked unconscious and abducted, awakening in The Village for another episode.

He wanted to get away to a desert island, somewhere that he could be his own master, but now he is caught in an uncanny tourist trap where the time share investment presentation never ends.

The show ran for seventeen episodes, becoming less real and more fantastic during its single season. The final episode was pure metaphor, so controversial that the ITV switchboards were flooded with complaints. Patrick McGoohan, the star of the show, received threats, while his children were bullied at school. This brush with toxic fame, a familiar trope of our time, is emblematic of how prescient the series remains today.

The first episode, “Arrival,” establishes the rule that Number 6 can never leave The Village. Later in the series, he does manage to escape — only to be returned to The Village by the same agency from which he had resigned, for the entire world seems to be in on the conspiracy. A mysterious white ball, Rover, will appear from time to time, suffocating and subduing anyone who makes trouble. Leaving is not an option; the world keeps him here through rules and means that are beyond his ability to even understand, like a person filling out their own tax forms.

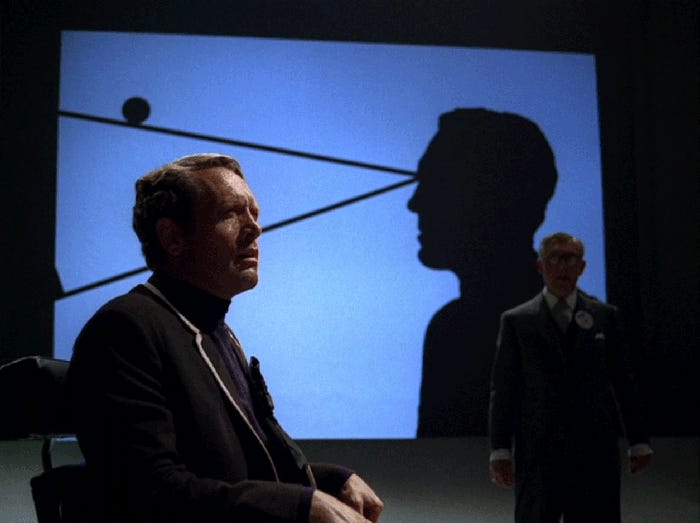

The Village demands to know his mind, the last place where anyone is free. Throughout the run of the show, an ever-changing series of administrators hold the position of Number 2 on behalf of the unseen master of the Village. Eric Portman, a legend of early British television, portrays the incumbent Number 2 in “Free For All.”

Having demonstrated their complete power over the prisoner, in this episode The System offers its prisoner a chance to win political power. ‘The System’ holds him in the softest, most reasonable grip. If he wins, he will learn the identity of Number 1.

“Everybody votes for a dictator,” Portman tells McGoohan, but politicians are in fact defined by the limits of their powers.

You can see the full episode here. Because no other episode touches directly on politics, however, it is not necessary to watch any other episode than “Free For All” in order to understand The System of The Village.

The prisoner is clear-eyed about the offer. “I shall be running in this ‘election,’” McGoohan tells the residents of The Village with smoldering irony. He treats the process as a circus and becomes the perfect electoral clown. “Keep going, they love it,” Number 2 says when McGoohan insults the “rotten cabbages” in his audience, the participants in The System who are too weak and craven to resist, to rise up, to refuse orders.

Number 6 vows to “discover who are the prisoners and who the warders.” Yet like an Eldritch ring of power, The System imprints its own values on anyone who would control The System. Put simply, The System of democracy in The Village — its constitution — changes people more than it is changed by them.

Number 2 praises his “militant and individualistic” opponent. It is to be a refreshing change of pace, as politics have become too boring in a happy society. A “unanimous majority” is “very bad for morale,” Number 2 says. Partisanship is itself a form of progress: the people deserve a real choice.

Number 6 repeats his defiant performance at the Town Hall, only to suddenly undergo brainwashing in the process of becoming a viable candidate. He is spun around by the process, a prisoner of the political circus.

Number 6 is never really in charge of his own message. Signs appear the instant his first speech ends, one of several discordant and bewildering moments that shake the character and the viewers into compliance. We are all being hypnotized into accepting a new normal.

Standing in the council chamber under the bright light of examination, Number 6 loses control of his actions, and then with the aid of a political consultant, loses control of his tongue. He speaks thereafter in talking points.

He also adopts the characteristic salute of The Village, a sinister farewell in a surveillance state: “be seeing you.” He remains the authoritative voice of change, though what exactly he will change is left quite unclear, because “change” has become a metaphor for the man. A slogan like ‘hope’ or ‘joy,’ evidence that a branding consultancy has massaged the message.

“You thought if you won and took over our village, you would be able to control an organised breakout, correct? Good,” the consultant, a civil servant according to dialogue in the control room, tells the prisoner-candidate. “But this was a mistake, wasn't it? You are on the side of the people, aren't you? You mustn’t think only of yourself. You have a responsibility.”

Great power comes with great responsibility, they say. You owe the people good governance.

Because political parties must be relatively few in number, regardless of the specific electoral system — see Duverger's law — differences of opinion on some issues must always be incorporated into one party and candidate. This is replicated in the mind of a party voter. Liberal cognition holds two points of view at once and resolves the cognitive dissonance as partisanship: Vote for Candidate X because you support the Agenda of Party Z. Vote for Candidate X because you don’t want Candidate Y and the W Party to win, do you? Their agenda is terrible! We should set aside these minor, petty issues of disagreement until after we win the election.

Furthermore, to be a Man of the People, a would-be dictator of the people must be seen to appeal to all of the people, the full demos. How else is Number 6 to make any changes to The Village unless the people choose to put him in office, first?

Before he can win, Candidate X must unite Party Z, because the party decides who will represent it. A political party literally has no other reason to exist than to pick candidates to represent it in elections so that we, the demos, are spared the work of choosing candidates to choose from. Democracy only works when there are parties to represent broader agendas and create coalitions: may the larger coalition win.

The Village holds annual elections. “We choose every twelve months,” Number 2 tells his prisoner. “Citizens have a choice,” he says, and that is true, but the frequent election results in a weak executive. Limited executive terms are usually intended to prevent the accumulation of power or graft. American presidents, for example, are term-limited by the Twenty-second Amendment of the Constitution so that they do not make too many unwanted changes that will last too long.

Inasmuch as the crowd shouts for “Progress! Progress! Progress,” the ideal democracy never really changes very much, so that the people enjoy their prosperity.

The campaign itself is a sudden noisy season of partisanship, guaranteeing minimal voter appreciation of the nuance of policy arguments. The constitution of The Village is biased against change from the outset of any candidacy.

“If you win, Number 1 will no longer be a mystery to you,” the prisoner is told. Upon his awakening in office as Number 2, the prisoner finds that constitutions and structures limit his powers as well as his time, expertise, and authority to make changes. He is a prisoner of his democratic society, after all.

As for the identity of Number 1, he already knows it. But how well does any man really know himself? That sums up the rest of the series.

“Think globally, act locally”: the motto of the ‘global citizen’ living in the ‘global village’ speaks to how the post-Cold War global order seemingly shrank the world to a single ruleset for a time, not simply leaving the United States as a global hegemon, but also locking everyone into a single, global supply-chain, with global finance — capitalists — calling all the shots. It was a world in which Thomas P.M. Barnett could write seriously of “closing the gap” to bring the entire planet into a single rules-based international order. World peace, basically.

Some people rejected this emerging world order with violence. They said “no” to a worldwide System defined by GDP and monetary values alone. Anarchists at the 1999 Seattle protests against the World Trade Organization heralded a revived revolution on the left. Arch-globalist Thomas Friedman refused to even entertain their ideas. The destruction of the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001, subsequent state-breaking in the Middle East, Iranian proxy warfare, and the Russian invasions of Ukraine have all torn the edges of the post-Cold War world order. America seems to have spent its strength of will in Middle Eastern adventures. China struts around drawing its Nine-dash line on maps, redrawing the world order in their image. ‘Decoupling’ from Beijing has become the new security paradigm.

Turns out, in the third decade of our century, that there is no global democracy, no ‘global village,’ after all, much like the planet was just before both World Wars, when ‘global public opinion’ also turned out to be vaporware. Nonprofit organizations promised to fill the gap by representing the unrepresented, but they really represent themselves alone. The autistic anger of Greta Thunberg was supposed to represent the planet’s youth when she in fact represents a rarefied view from nowhere. Klaus Schwab wants to house humanity in automated timeshare apartment pods and feed us bug protein, a lifestyle no one asked for. Our 21st century global elite gathers at Davos from across the world flying in jets to decide how we, the great unwashed, will be denied air travel in order to save the planet. Occupy Wall Street transmuted into the greenwashing of Wall Street.

What makes The Prisoner worth watching nearly six decades later is its conceit of a man who knows too much already, who demands to know the rest, who refuses to surrender his personhood to a depersonalizing System, or to change or adapt to new rules imposed on him without his consent. Number 6 is seen first in his kit car, a machine he has built with his own hands, enjoying the freedom of the road. Something about McGoohan’s Number 6 has always resonated with the libertarian ethos that questions the necessity of laws, agencies, and even The System itself.

Even the word ‘globalization’ or the phrase ‘world order’ is bound to raise conspiratorial hackles because they carry cross-border political implications. Beginning first with the Reform Party of Ross Perot and the aborted 2000 presidential candidacy of Donald Trump, the word ‘globalist’ has registered the discontent of an increasing section of America that rejects the burdens of hegemonic globalization. They want America to be great again, and also powerful, but they do not want to feel as though the security of the entire globe is the permanent responsibility of Americans, all the time.

To use a phrase properly, the Trump majority wants a new world order in which the United States shares the project of global security more equitably, especially with Europe but everyone else as well. Occupying the whole of the globe with hundreds of military bases has costs in blood and treasure, and this price should either reduce, or pay back to America in a more direct form, according to the anti-globalist.

They also reject the ecumenical project of the borderless Global Village. “She doesn’t even speak English,” McGoohan’s Number 6 complains. He is unhappy with Number 58, the woman assigned as his campaign assistant. This woman “speaks in an invented foreign language, but every single word of it is specified exactly in the script — in what the actress playing the maid, Rachel Herbert, called McGoohanese,” Gareth Roberts writes at the Culture Bunker. “It sounds vaguely, non-specifically Eastern European,” altogether unfamiliar to everyone.

Definitely an immigrant from somewhere, who knows? Wherever she is from, he sees her as an imposition. Roberts:

Remember that the writers’ guide compiled by [George] Markstein makes great play of the multilingual character of the ‘international’ Village, as does the script of ‘Arrival’. Here McGoohan seems to have created, however loosely, a structured linguistic system for the character - ‘pasna’, for example, seems to mean ‘understand’. It’s not just rhubarb.

In the script she says ‘tic tic’ not just in the Living Space at the end but at the end of Act 1 and elsewhere, which suggests it’s McGoohanese for ‘six’. Another cut line has the Supervisor tell Number 2 that her tongue is ‘Not one of my languages’, which could be delivered any number of ways. Is it supposed to be the real language of an invented country, one of those fictional Baltic Soviet states that ITC shows often feature?

But what is the point of the maid in the Village’s plan this week? She is, as we will later discover, actually another number 2 all along, and very English-sounding.

Spoiler alert: every successful revolution becomes a new establishment. Every generation seeks to overturn the old and speaks its own political language. Prime ministers are turfed out by self-starting backbenchers and reality television stars become President of the United States. World orders are overturned while everything somehow remains the same.

We want change, but not the kind we dislike. We all want someone else — a leader — to fix all the problems that are too big for us to solve, but we also all want to limit that leader’s power over ourselves.

One might dismiss this as postmodern despair. Democracy and voting, its sacred rite, are revealed as oppressive forces upon the individual, whatever the system, especially when the individual is trying to change The System for the better, from within. Democracy is a trap. Escape is impossible because the residents of The Village do not want to escape. Powers are always limited, frustrating genuine change. Is freedom an illusion?

But this conclusion ignores the rest of the series. The Village is the illusion: it is someone’s table model at Davos, a cardboard masterpiece of the sustainable, data-driven, carbon-zero community of the future living in perfect harmony with nature, that will never be concrete because it fits natively Nowhere: the Greek word ‘utopia’ literally means nowhere.

American political scientist Benjamin Barber’s pessimistic view, contained in the title of his 1995 book Jihad vs. McWorld: How Globalism and Tribalism Are Reshaping the World, was that unfettered global capitalism and local cultural reactions to it would challenge the very foundations of western liberal democracy. We may look to the 2024 presidential election result, in which Donald Trump won a popular majority, as evidence he was correct, and that the alternative offered by the Democratic Party was more in line with a view from nowhere.

A year after Barber’s book was published, Samuel Huntington predicted in The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of Global Order that the wars of the 21st century would be waged over competing identities in a borderless world. The age of terrorism has resembled the predictions of globalization’s critics.

There is no single human community, and no single set of rules will ever fit every human community, nor every individual, for we are too diverse in too many ways. Global democracy is impossible because every local democracy is questionable. Democracy is quite capable of electing dictators and imposing oppression. We live in many villages, all different, not a single village that is the same, while the vastness of cities and landscapes can swallow us up and render us anonymous again. The series ends with McGoohan in London once more, free to be. He is Number 1, still a prisoner under Big Ben.