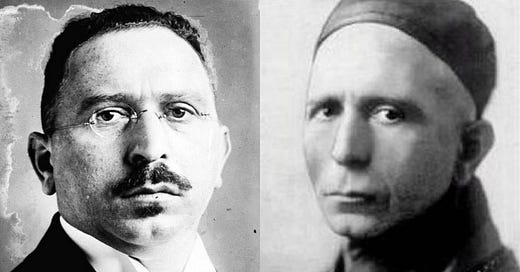

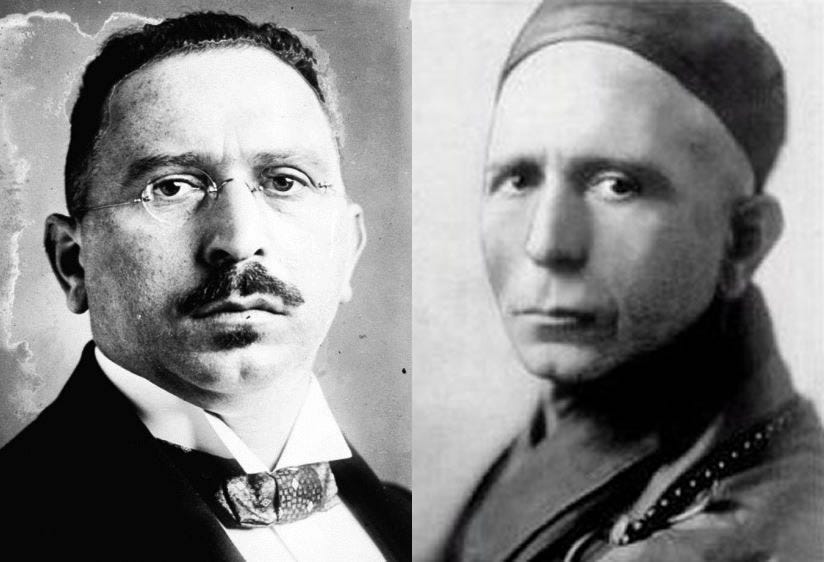

Change Artist: One Man's Long, Strange Trip Around the World in Search of His 'True Self'

A tale of modernity and 'authenticity'

“Two strains of mind and action have always been in conflict in my life,” Ignatius Timothy Trebitsch-Lincoln wrote in the opening of his dubious jailhouse memoir, Revelations of an International Spy. “In one of them predominates the quiet fervor of the mystic and the imaginative sensitiveness of the artist. In the other, craving for excitement, passion …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Osborne Ink to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.